by Shirley Seale.

1914 was not a good year in the Hawkesbury. There was a serious drought which had begun in 1911 and was not to end until 1916 and as this was a farming area, the continual dry weather would have been a great worry to families dependent on livestock or crops. A butchers’ strike in March would have adversely affected the wages in the town of Riverstone where many of the men worked at the meatworks. There were five trains a day to and from the city from Riverstone and horses and carts were the common forms of transport, although cars were making an appearance. The recommended basic wage for a family of four was 2 pounds 8 shillings a week. Since a Speedwell bicycle cost 8 pounds 10 shillings, almost 4 times that amount and a wristlet watch was 4 pounds or almost 2 weeks wages for a family, people were not conspicuous consumers of luxuries. An unskilled labourer was paid 8 shillings and 6 pence a day for a six day week.

Local people had a lot to think about just keeping their lives together and the rumblings about trouble in the Balkans would not have had a high priority. However we were still proud sons and daughters of the Empire. We were taught English history, not Australian, in our schools and we had “God Save the King” as our national Anthem. Our king was George V. We celebrated Empire Day on 24th May, Queen Victoria’s birthday, each year with special school assemblies, later a half day holiday and fireworks. When war was declared on 3rd August 1914, the Prime Minister declared, “When England is at war, Australia is at war!” Two weeks later when he had been ousted at an election, the new Labor Prime Minister, Andrew Fisher declaimed, “We will defend the Mother Country to the last man and the last shilling”. England accepted the offer made by the P.M. of 20,000 men in the Australian Imperial Force and 10,000 had enlisted in Sydney alone by the 20th August.

So how did Riverstone people learn about the war? It took nearly three weeks for the Windsor Richmond Gazette to mention it, on 28th August, the Sydney Morning Herald, would have news, but the telegraph wire service did go to the railway station, which also housed the post office at Riverstone and from there word would have spread by word of mouth. For us, with our instant access to news from around the world as it happens, together with graphic pictures, this slow dissemination of knowledge is hard to grasp. Our population was between 4 and 5 million at the start of the war, not counting the Aboriginal people. Duntroon Military College had opened in 1911 but it took four years to train an officer, so the first trainees had not yet graduated.

Patriotic fervour swept the land and eager young men, to whom it seemed a wonderful adventure hurried to enlist. All told 416,809 enlisted in the course of the war, about one tenth of our total population. Most of them were tradesmen aged between 21 and 30 years of age and 81% were single. By the end of the war 60,284 had died and one in two families had suffered a bereavement. There were not enough trained men in Australia to train the recruits and they were sent to Egypt for training. The first 38 ship loads left from St George’s Sound in WA on 1st November 1914. Enlisted recruits were paid 6 shillings a day, all found. The cost of the war was so great that in 1915 income tax was introduced for the first time. 4 million pounds was raised in 1915/16 rising to 10 million by 1918/19. Still by the end of the war Australia’s debt was 291 million, and NSW had to find almost 2 million pounds to fund the 65,165 war pensions that were granted. The war took a heavy toll from everyone.

Recruiting

At first young men rushed to join up. They were swept up in the patriotic fervour that enveloped the country. However as reports and letters came back home from those who had been first to go, the enthusiasm waned and earnest appeals were made for more men. Riverstone held a huge and enthusiastic recruiting rally at Riverstone Meatworks on Tuesday, 16th November 1915. Mr J.P. Quinn presided. Speakers were Mr R. Atkinson Price MLA, Corporal McQueen and Quartermaster O’Brien, both of the latter having recently returned from Gallipoli. The meatworks management promised to reinstate them when they returned and to make up the difference in their salaries.

The speakers called for volunteers to go and fight and eleven young men handed in their names. They were John Robbins, Joseph and Leo Birtle, Robert Case, Stanley and Cecil Alcorn, Jack Towers, Joseph Green, Frank Keegan, George Croft, T. Humphries and Fred Hurley. It was proposed by Joe Birtle and seconded by John Robbins that a route march from Riverstone and district to Sydney be organised. This was carried unanimously. The meeting was considered to be the best ever held in Riverstone. Within days three other lads had enlisted although their names are not given. There is no further information on whether the march took place or if the impetus was lost after the meeting ended.

And what happened to these volunteers? John Robbins, known as Jack, a promising cricketer whose father had instructed the local rifle club in drill at the outbreak of war, was sadly killed in action in France. His brother Eric was wounded but returned safely. The Alcorns and Frank Keegan and Fred Hurley were welcomed home as were Jack Towers and Joe Green, although they were wounded and their welcome home was delayed.

Posters were made to encourage women to urge their men to enlist, and to stir up the younger lads, 200 boys under 18 who were too young to fight were marched to towns around the Hawkesbury area, including Riverstone. They were called “Boomerangs” in the hope that they would return safely home again.

Empty Saddle Clubs were formed and at large gatherings such as the Windsor and Riverstone Agricultural Shows, horses with saddles but no riders were led into the arena and willing men leapt up into the saddle where they were immediately processed by recruiting officers. They were attempting to fill the Hawkesbury Light Horse numbers and the men were promised that they would train and stay together. This was great for morale but had a devastating effect on the district when a unit was involved in a battle and many friends and brothers were killed and wounded on the same day.

As films were available these were shown. At Riverstone Picture hall, Lt Church an Anzac, showed pictures of “The Landing”, “Charging the Cliffs” and “Lone Pine” and told the tale of our boys outwitting the wily Turks.

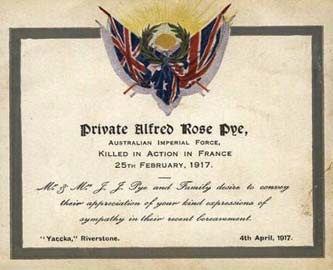

Other names from the district to enlist were Ambrose Mason, Charlie Fisher, Jack Conway, the Alcorn brothers, the Alderton brothers, the Schofields, the Draytons, the Kennys, the Pyes, Robert Jones, Claude Voysey, Joseph Brown, Ernie Marlin, John Jones, F Hayward, J Wiggins, Eric Robbins, Gunner Witts, George and William Teale, Cecil Greenshaw, Rupert Vidler, Robert Rankin, Alex Stubbs, George Stell, Harry Smith and J Pollard. Many of these kept in touch during the war and were able to give each others families news of their loved ones

Women’s Role

In 1914, women were still in corsets and long dresses. They were still largely under the protection and the thumbs of their fathers, brothers and husbands. Very few women worked outside the home and they were not encouraged to think of a career. There were women school teachers, nurses and shop assistants. When war was declared the women too wanted to be involved.

2139 nurses served abroad as members of the Australian Army Nursing Service, but women doctors, few as they were, did not get appointments as it was considered it would be too much for them! 130 nurses were seconded to the British Army and 22 masseuses were sent overseas. Before the war ended, the shortage of available men had seen women employed for the first time in banks, the Public Service and insurance companies. The first policewomen were also appointed, but they were all expected to give up these jobs and go back home when the war was over and the men returned. Women offered their services as ambulance drivers and cooks but were not accepted. They formed the Australian Women’s Service Corps and offered to take on jobs at home to release men for overseas service but were rejected. However most of the work done by women in the First World War was voluntary and unpaid.

One of the things they did was join the Red Cross. Riverstone formed a branch in September 1914 under the Presidency of Mrs Anstey, the headmaster’s wife. Mr Cohen, a local storekeeper, donated a roll of flannelette for their use. It was necessary for the Red Cross to assist in sending comforts to the troops as they were very poorly supplied. Each soldier was issued with only three pairs of socks and in the trenches, when everything was wet this was not enough. Women knitted as much as they could. Rosemary Phillis of Riverstone says her grandmother, Ida Rumery, recalled knitting socks for the Home Comforts’ Fund. They knitted even as they walked around the house. The leg and foot were no problem but shaping the heel was very difficult. Later as steel for knitting needles became scarce, the women used bicycle spokes instead. My Aunt Muriel did that. Altogether the Red Cross forwarded 1 million pairs of socks to the soldiers during the war. Sometimes they would tuck a note into the toe of the socks they knitted and often received a reply from a grateful soldier.

All sorts of events were held to raise funds, for the women sent tobacco, reading materials and extra food and warm clothing too. A cricket match was held at Riverstone between the young men and the ladies of the district. The men, to ensure that the ladies were not at a disadvantage, played with their opposite hands and used stumps and pick axe handles as bats!

When the people at home were told what a difference sandbags made for safety around the gun emplacements, these too were added to the things that were sent. One of the most enthusiastic young women in this area was Miss Matilda McCabe, a Riverstone schoolteacher, who formed a first aid class, and had taken part with gusto at every community function organised in the district. As First Aid trainer she had 25 women and girls in her team and, dressed in nurses’ uniforms, they often formed a guard of honour with arches of flowers for the enlisting soldiers to walk through at the community farewells. She announced she was going to England to nurse the soldiers and was presented with a gold watch and other gifts at a farewell. But true to the limitations placed on young women in those days, her mother’s dying wish was that she should remain at home to nurse her brothers if they came home from war wounded, so she stayed at home.

Riverstone women also had organised a Home Comforts’ fund and in 1916, when the troops were fighting in the cold trenches of France, had handed the mayor a parcel of winter clothing. This often included sheepskin vests and soldiers wrote home expressing appreciation of the goods sent to them. About now, the recipe for Anzac biscuits was circulated as a treat which could be sent in tins to the troops without deteriorating. Patriotic Funds were organised throughout the district and many social functions were held to raise money for the boys at the front. By this time the realities of war were being felt in Riverstone and some of the money raised was set aside for the widow and family of Private James Symons who had been killed in battle.

Another local woman, Maude Butler, who had been refused enlistment as a nurse, made news as she travelled to Sydney, persuaded a barber over his own judgement to cut off all her hair, bought a uniform from a willing soldier, purchased puttees and belt and climbed the stern rope of the troop ship after dark. She remained hidden for three days when hunger forced her out. She was transferred at sea to another boat returning to Melbourne, where she was again dressed as a girl and returned to Sydney. Two months later she did it all again! This time she had to give an undertaking to stay home. She only wanted to be a nurse she said, and if she had been a man she could have gone to the front. “One must admire the girl’s persistence”, wrote the Gazette, “it contrasts with the able bodied shirkers who are so numerous in city and country alike”.

Farewells

Each local community felt the urge to farewell their recruits in a memorable way. Functions were given at Vineyard and Kurrajong, Marsden Park, Schofields, Windsor, Wilberforce, Kellyville and Riverstone. At each function the troops being farewelled were presented with gifts to take with them to remember the best wishes of their friends and families at home. Among the gifts presented were; wristlet watches, wallets, pocket testaments, pipes, sheepskin vests, fountain pens, and shaving kits. In Riverstone the farewell evenings were usually held at the Oddfellows Hall, and most of the residents were present.

The hall would be decorated with flags, Chinese lanterns and crinkled paper. Typically there was a concert held first, followed by supper and then the presentations. The local dignitaries were present and often a career soldier from Sydney addressed the meeting. Sometimes it took the form of a fancy dress dance with people typically dressed as Britannia, France, Russia, Australia etc. Patriotic songs were sung by local soloists such as Mr Teale, Misses Cole, Bell and Griffin. Recitations were given and after supper, dancing continued until 2.30a.m.

At a farewell evening held at Riverstone in August 1915, after Mr Kiss of Clydesdale had wished the recruits good luck and a safe return, hoping that their noble example would be followed by others, Staff Sergeant Major Harvey of Victoria Barracks spoke in a much more sombre note. “These men” he said, “were the best in the district. Britain wanted all the men she could get. So far 30 men had enlisted from Riverstone. It took 2 tons of lead to kill a man and 1 in 10 die on the battlefield”.

Not deterred by the statistics, Edwin Schofield, on behalf of those going off to the battlefield, said they would do their best and hoped to return crowned in glory and they would not disgrace their land. He later became a Lance Corporal. Later, Edwin and his brothers Aubrey and Horace were given another farewell by the Loyal Pride of Riverstone Lodge, where he was presented with his second set of pipes, and was assured by Brother Vaughan that the Lodge would keep them all financial during the war and if they were disabled or numbered among the fallen they would receive full benefits. Once again Edwin replied on behalf of the others and said he felt it his duty to enlist and called upon all unencumbered men to do the same. He would like to see it ended before he was called upon to take life, but if wanted he hoped he would be able to do his duty for the Empire. Toasts were made to the soldiers and their parents. Aub and Edwin returned safely, but Horace was killed in action in November 1916 and the same community turned out for a memorial service in his honour.

In June of 1916 a Soldiers’ Presentation Committee organised a musical evening and presentation; with the watches being presented they were told that as they reflected the time the faces would remind them of the faces of their friends and well wishers assembled.

Private Fletcher a teacher, was given afternoon tea by staff and former pupils at Riverstone school. He returned safely to resume his job. And so the lads from Riverstone left to do their best for their country, strengthened by the community’s good wishes,

Stories and Letters.

Most of the local lads had never travelled far from home before and started off to see the world. Private Herbert Davis of Riverstone had sent his parents 800 views and photographs – in fact so eager was he to document everything he saw, that his camera was taken from him for a while. He had survived Gallipoli but was later wounded in the Dardanelles.

As news was hard to come by for those with family at the front many parents gave the letters they received to the local paper to be printed in full for others to read. William Teale of Riverstone was a frequent, descriptive writer. On the way over on the troopship, he had won the heavyweight boxing championship He turned 21 in Egypt and told his parents he had reached 6 feet in height. He said he wasn’t sorry to leave Egypt as he never wanted to see another place like it. But in his next letter he moaned “They put us in an even worse place — Arabia. It isn’t even fit for the natives who live here. All you see is sky and desert where we had our trenches. Flies in millions- 130 degrees in the shade and one pint of water a day! When next he wrote he had wonderful news for his parents. While in Malta for a couple of days there were three other boats in harbour and he signalled with flags to see if his brother was on board any of them. He was. The ships were 1/2 a mile apart but he swam over and pulled himself up on a rope. “George nearly fell overboard when he saw me”. They chatted for 1/2 an hour then George’s boat left and no one knew where they were going. Will later went to France where ” the fire from the guns make it as light as day and they make the ground shake”. Will got back home safely but George lost his right eye in France.

Another local family to receive lots of letters were the Kennys. Bert Kenny had worked at the rneat works and had left with the 2nd Light Horse in June 1915. He had been shipped along with the horses and the weather in the Great Australian Bight had been so bad that some of the horses got influenza and died. The boat was declared unfit for horses and they were taken off at Fremantle. Bert wrote about the scenery in Suez and was surprised by the fertile country and to see donkeys and camels being used as we would use horses. Bert Kenny developed diphtheria while overseas, and when he returned home, the Gallipoli Star he had been given by a grateful wounded Turk he had assisted was put on display in Davis hardware store. His brother Jack was wounded in Heliopolis after six weeks in the trenches and after some weeks recuperating was sent home. There he was persuaded to write about his time in Gallipoli for the paper. “On 19th August we were issued with … rations, ammunition and water. It weighed about 100 pounds in all … we were disappointed at not being able to see the enemy although … I saw a good many of their dead lying in front of the trenches, a result of an attack made a week before… For a good time only 27 feet separated us from the Turks … Were trenches are so close hand grenades are largely used by both sides … when one does succeed in getting into our trenches it is customary to throw a blanket or coat over the grenade and lay flat on the ground, trusting to luck, but the explosion causes a great rush of air into the lungs of those around, frequently bringing on a haemorage (sic) of the lungs”. Jack re-enlisted when he recovered and eventually returned home safe.

Ambrose Mason had been studying to be a teacher when he enlisted. He wrote home in August 1916 to say he couldn’t believe that he had picked up a copy of the Windsor and Richmond Gazette on the battlefields of France. It was like meeting an old friend, he said. A short time later, Harry Turnbull wrote to his family from a hospital in Wales to say that he had heard that an A. Mason had been killed. Such was the communication of the day that it was some time before the family was notified that it was true. His mother wrote to the Red Cross for confirmation or otherwise. Ambrose, by this time a corporal on the Western Front, had gone with others to secure an enemy machine gun and had never come back. It was a long time before their bodies were found. He had sent his mother a postcard on which he had jokingly written .”We will all be dead soon”. In August of 1919, a memorial font was dedicated to his memory at St John’s Catholic Church at Riverstone. It is now in the possession of a family member.

Mail came in various ways. Jessie Alderton of Schofields received a message by “bottle post” from the brother who sailed in 1916. “Just a line over the water”, it said. “I have not been sick and am as happy as a king and if this finds you, keep it to remember it as a swimming note, so I now send it overboard. Your loving brother Harold”. The bottle was found on a beach at Ram Head in Victoria and sent on by the finder. Harold later lost an eye , but returned home.

The local boys told it as it was when they could get through the censorship, and one letter really brings home the terrible hardships they were going through in the trenches. George Teale of Riverstone wrote on Christmas day, 1916, “we have just finished our dinner. We had some stew and a piece of plum pudding and a packet of biscuits, so we made the best of things. The pudding was not bad only we had to get a piece of string to pull it out of our jaws, it was that sticky,… The big guns never stop they are going day and night. They sent Fritz over his Christmas dinner today. There was a big bombardment. It is very wet over here,… plenty of snow, plenty of mud, plenty of shells. Did little Arthur and Fred hang up their stockings for Christmas? I hang mine up every night full of water.” Is it any wonder the ladies kept knitting socks? George was later gassed, lost his right eye, but returned.

How lucky we are that families kept these letters and cards and that the Windsor and Richmond Gazette published so many of them during the war years for all to read.

Returning Heroes Welcomed Home

The district folk were looking forward to welcoming back to their midst the sons who had fought for their country. The various lodges, the Patriotic committee and the specially formed “Welcome Home Committee” made sure that each soldier was met with suitable celebration when at last he returned. First the ladies decorated the railway station, usually Riverstone as the main station in the area, but sometimes Schofields Siding if the soldier had come from that district. The station was covered with bunting and greenery and flags and sometimes the colour scheme was chosen to match the battalion colours. A huge crowd always was there to cheer the homecoming hero.

News travelled fast in the small community and the families were notified in advance of the date of arrival. At first only one or two soldiers arrived, but after peace was declared and the war was truly over, by 1919 as many as a dozen troops would be on a train, and the railway had to put a limit on the number of people who could squash on to the platform. There were speeches at the station and almost always Mr J East, who owned the Royal Hotel at Riverstone, offered his car to be decorated and used to convey the soldiers to their homes in style. A formal celebration and welcome home was held at a later date in the evening. The whole town turned out to welcome Fred Wiggins and his “Pommy” bride, the first war bride to come to the district. She was given a bunch of flowers as she alighted from the train to her new home.

One memorable welcome took place to welcome home the James, Schofields and Alderton boys. A banner was erected with the soldiers names shown in a horse shoe. The huge crowd admired the decorations which included Chinese lanterns, and Mr Kiss of Clydesdale drove them home in his decorated car. Sometimes a choir sang, schoolchildren often called to sing “Home Sweet Home”, or the Riverstone brass band under the direction of Otto Warters played suitable selections.

At the Oddfellows Hall or the Picture Hall, a celebration took place for the boys. There was a band, usually a concert and speeches praising the exploits of the troops, their modesty and patriotism. They were presented with inscribed gold medals and often with a kiss offered by lady relatives or friends. Above them were suspended on occasion, “tricky little bags”, which were punctured to release confetti on the recipients as they received their medals. Sometimes pretty girls were used to sprinkle the confetti instead. Then came a sumptuous supper and dancing and games until the small hours.

By 1918 the welcome home evenings were sharing with the farewell evenings for those going to the front to replace those coming home. By 1919 there were so many men returning to the district that it was decided to wait until 14 or so had returned and then hold a combined event for them. They were to be feted in the order their names appeared on the war Honour Roll.

The community felt a responsibility for those not at home and regular working bees were held to keep their farms and orchards in order, and volunteer labour was freely forthcoming along with monetary donations to build a house for the family of John Symons who did not return.

A very touching welcome home was given to Private E. Griffin of Marsden Park who returned after 4 years service. He had been an original Anzac and had left a wife and five children to do his bit. The following verses were composed by his wife and read by one of his children at his reception on 30th January 1919.

Today we are all so happy,

‘Cause our Daddy has come home-

From the fighting and the bloodshed,

From far across the foam.

We are proud of our soldier Daddy,

And the brave deeds he has done.

God bless our glorious A I F

And bring them safely home.

Then it was back to reality again for the diggers. No trauma counselling, no de-briefing, just back to work and family. Charles Knight and Jack Towers were so ill they had to be taken straight from the troopship to the military hospital. Charles had been wounded in the thigh a year previously and was still partly paralysed. Jack was still in critical condition two months after his return. However when he did return a joyful welcome was waiting with his house decorated with flags and his family out in force to welcome him home.

Many were shell shocked having seen their friends blown apart or buried alive in the trenches. Some from Riverstone committed suicide, unable to forget what they had lived through, Councillor Pye who spoke at many of the functions said they had come back from the “jaws of hell” and that they might look all right but 9 out of 10 of them were not all right and never would be all right again. However, following the war the Spanish flu epidemic hit hard and one local soldier’s wife who had travelled to meet him in Sydney was dead three days later. Alfred Brookes who had settled to poultry farming on his return was moved to resume his old job as warder at St Vincent’s Hospital to ease the staffing difficulties during the epidemic. The Gazette called it a “fine spirit of patriotism”.

The returning soldiers were careful to praise the local people who had kept them supplied with comforts and Christmas parcels while overseas. In the Riverstone area the troops had special framed “Thank You” boards made for the women who had supported them. They had medallion photographs of the men and two of the boards can be seen in the Riverstone Museum.

Memorials and Honour Rolls

Each community wanted to honour in a permanent way the men who had given their lives or years out of their lives to preserve the Empire. Plans were underway for these memorials and money was being collected long before the war ended. Kellyville erected a panel of maple under glass, with the names of 32 local soldiers, on the outside wall of the school where it could be read by those travelling by.

Riverstone collected for an Honour Roll and raised 60 pounds at a meeting held at the Picture Hall. It was planned to erect a temporary board in the waiting room at the railway station. This was unveiled by R.B. Walker MLA in October 1918. There were 128 names on the board with more to be added. The local band played, speeches were made by Councillor Pye, Mayor Chandler, Ensign Jones of the Salvation Army and others, and the ceremony was followed by refreshments at the Oddfellows hall. The Oddfellows Lodge had their own Honour Roll as did many firms and associations locally.

By March of 1919 The Memorial Committee of Riverstone, with Councillor Pye as Chairman, had raised 50 pounds for a permanent memorial to honour the dead of the district, and were hoping to raise 50 more. The railway department had approved the use of land outside the entrance to Riverstone Railway Station as the location for the monument. It eventually was to hold 22 names and was opened with great ceremony by R.B. Walker MLA on a blistering hot day on the 8th of November 1919. The monument still stands in its original place today and is viewed by the hundreds of people who use the station each day. It is the setting for the local Anzac Service each April.

Spoils of War

At the war’s end, all the towns and communities which had sent soldiers to battle, were presented with a trophy as a district memorial to the efforts of the citizens. These were distributed by the Australian War Memorial. Riverstone and district received a German machine gun of the Maxim type. This was claimed for the district by Lt Fred Hayward of Marsden Park. The gun was captured by Australians near Lille …. Mr Charles Davis followed through with the claim.

The gun was delivered to Riverstone Railway Station in April 1921, where one of the signatories for its safe arrival was Roderick Terry of Rouse Hill Estate. The gun was placed at Rouse Hill School where it remained until the 1960s as ex-pupils of the school recall. When the school residence was built the gun was removed and subsequently lost and at the time of writing has not been recovered.

References

- Video. 1918 Remembered. Chris Masters. ABC 1988

- Bassett, Jan. The Home Front. 1914 – 1918. South Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1988

- Video. The Christmas Truce. The History Channel 2002.

- Windsor and Richmond Gazette. 1914. Microfilm, Hawkesbury City Library.

- Bartlett, Norman. Australia at Arms. Canberra, Australian War Memorial, 1962.

- Gow, Rod and Wendy, and Birch, Val. World War 1. Hawkesbury Heroes. Volumes 1 and 2. Rod and Wendy Gow. Publishers. Cundletown. 2001.

- Macquarie Book of Events.

- Bowd, D.G. Hawkesbury Journey. North Sydney, Library of Australian History. N.d.

- Ardley, Daisy. Kellyville a Pleasant Village.

- Everett, Suzanne. World War 1. Sydney, A.P. Publishing. N.d.

- Matthews, Tony. Crosses. Australian Soldiers in the Great War. Brisbane,

Bollarang Publications, 1987.

- Riverstone Public School Centenary Booklet. 1983.

- Odgers, George. Diggers. The Australian Army, June 1860 – 5/6/1944. Sydney,

Lansdowne Press. 2000.

- Morrissey, David. Two World Wars. Macmillan 1986. A Children’s History of Australia Series.

- Video. Australia in World War 1. Australian War Memorial. 1997.

- Members of the Riverstone Historical Society, who contributed memories of their families, postcards and photographs which made the era come to life.

NOTE

For the entire text of the letters quoted, and for information on the soldiers and their families in the Great War in this district, I recommend the two volumes of Hawkesbury Heroes, where the Gows have indexed the excerpts from the Windsor and Richmond Gazette for the war years. Further information can be obtained from the Riverstone Museum.