by Judith Lewis OAM

I would like to sincerely thank the Lane family for giving me the opportunity to “meet” George and write this article. I hope readers will be as inspired as I have been by George’s story. He must have been a very special person.

The Early Years

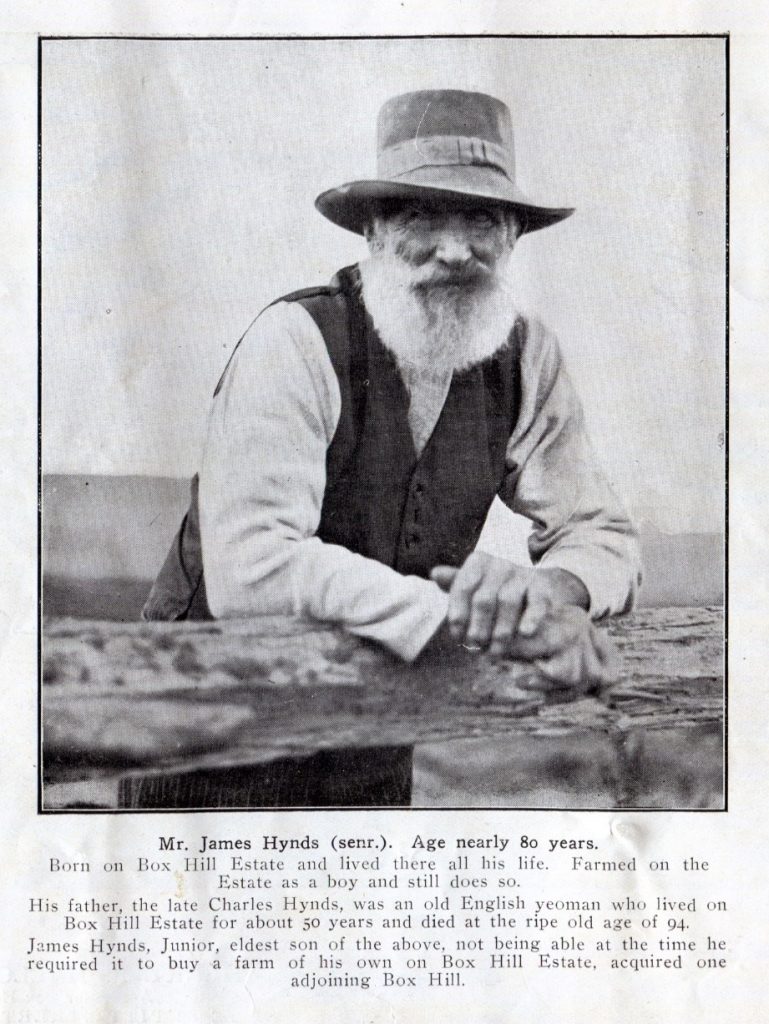

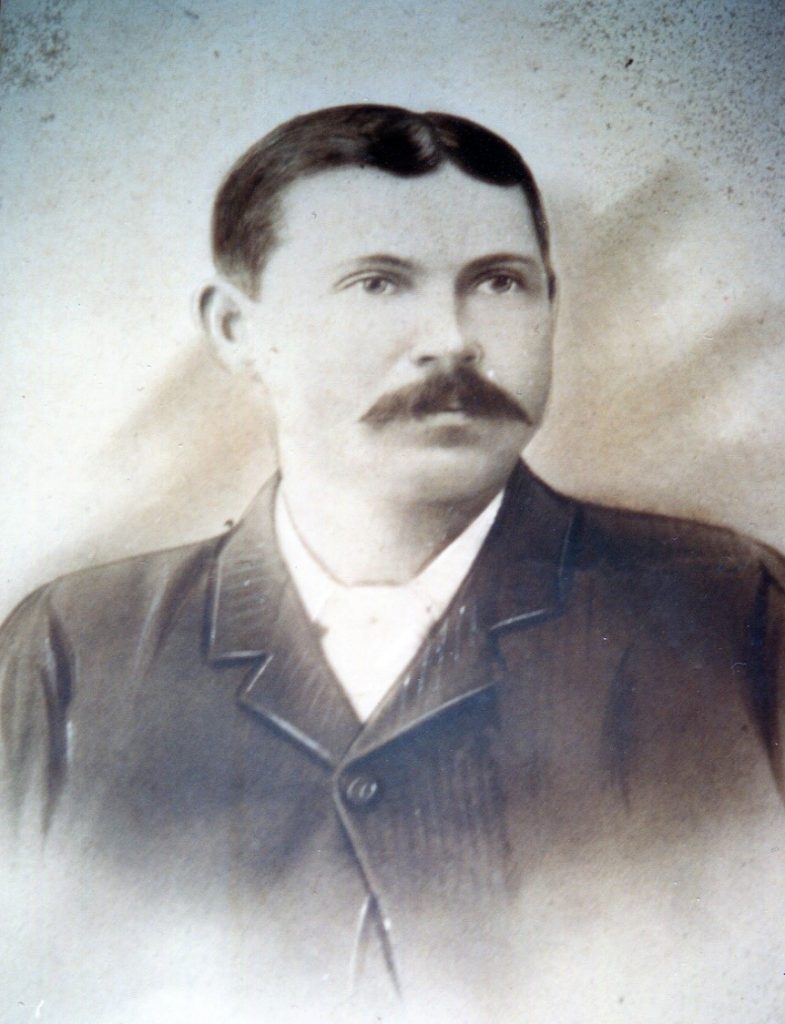

George Lane was born on 7 July 1936, a first child for Mavis and Sam Lane of Schofields. He was born at Ennislaun Private Hospital (now the surgery of Drs. Dixon and Longworth). George’s early childhood was typical of that era. He attended Schofields Public School, spent lots of time outdoors playing with mates and helping his father on their two acres of land in Station Street (now Bridge Street). He commenced his high school years in January 1948 at Parramatta Junior Boys’ High School, near the railway station (This later became Macquarie Boys’ High and moved to Rydalmere.)

Miriam (on stool). Sam is not in the photo and Laurie was not yet born.

It was in 1948 that George’s life was to change dramatically. The family had now grown to include Ruth (1938), Doreen (1941), Miriam (1943), Lyn (1946) and Laurie (1948). The family first noticed swelling in George’s feet. He was diagnosed as having “flat feet” and prescribed special shoes. When swelling also began in his knees George was taken back to the orthopaedic specialist who advised them the condition was not orthopaedic but medical. The local doctor had George admitted to Windsor Hospital where, in December 1948, Rheumatoid Arthritis was the diagnosis. With George failing to make progress, after a few weeks, the request was made that he be transferred to the Children’s Hospital Camperdown.

Visiting hours at the hospital were 2pm to 4pm on Sundays and children were not allowed, so his sisters and brother were not allowed to see him. Mavis and Sam travelled every Sunday by steam train and tram to visit George. On special occasions the remaining five Lane children would also make the journey and “see” George from the lawn outside his 2nd floor window. George was in a ward of children from all parts of the state. (Some of those children who came from the country would rarely see their parents or have visitors.)

Ruth Tozer recalls her Christmas days at that time, “We would eat our lunch on the train then go to see George”. She laughingly told of the time when George said he would like a bunch of mistletoe for Christmas so her then boyfriend Brian Tozer picked a large bunch, which became much depleted by the time George received it because so many people they met kept requesting some!

Letters

On 20 November 1951 a four page letter, containing a flight information card and a Trans Oceanic Airways Pty. Ltd. serviette, was sent to George by Captain P.G. (Patrick Gordon who called himself “Bill”) Taylor, flying “Tahiti Star” on the Flying Boat Service between Sydney and Lord Howe Island. Rejected by the Australian Flying Corps Bill joined the RAF who awarded him with the Military Cross in July 1917. In 1933 and 1934 Bill flew, as second pilot and navigator, with Charles Kingsford Smith on flights between Australia and New Zealand. He was navigator for Charles Ulm between Australia and England in 1933. In 1934 Smithy and Taylor made the first Australia – U.S. flight in the “Lady Southern Cross”.

In 1935, flying between Australia and New Zealand the flight seemed doomed when part of the centre engine’s exhaust manifold broke off and damaged the starboard prop. Smithy closed down the starboard engine and Taylor climbed out on to the fuselage to collect oil in a thermos from the damaged engine to transfer to the port engine He did this six times before they landed safely at Mascot. He was awarded the Empire Gallantry Medal in 1937 and was knighted in 1954. PG Taylor had heard of George from “H.G. Davis”. We believe H.G. Davis was the husband of one of the hospital’s Social Workers who had spent much time with George

A story in the Sunday Herald on 1 June 1952 brought George more than a thousand letters from people in almost every part of Australia. A radio station offered George any of the records he heard and liked, children sent him records and workers at a Sydney confectionery factory subscribed £70 to buy him a radiogram. All this kindness set George thinking. NSW Premier, Mr. J. J. Cahill had opened the new John Williams Memorial Hospital at Wahroonga where young polio victims were to be given the chance to get fit. George had heard that if there was a nurses’ home there it would mean thirty extra patients could get treatment. George had ten shillings. He asked, if he gave his ten shillings, maybe some of the nice people who wrote to him might also do so. Thus the “George Lane Polio Appeal” was begun by the paper with Sydney Lord Mayor Ernie O’Dea, who had visited George, offering to be President of the Fund. (In 1958 it was reported that ideas George had worked out for small charity concerts and home entertainments had raised £1600 (almost $4000) for charity.)

Visitors

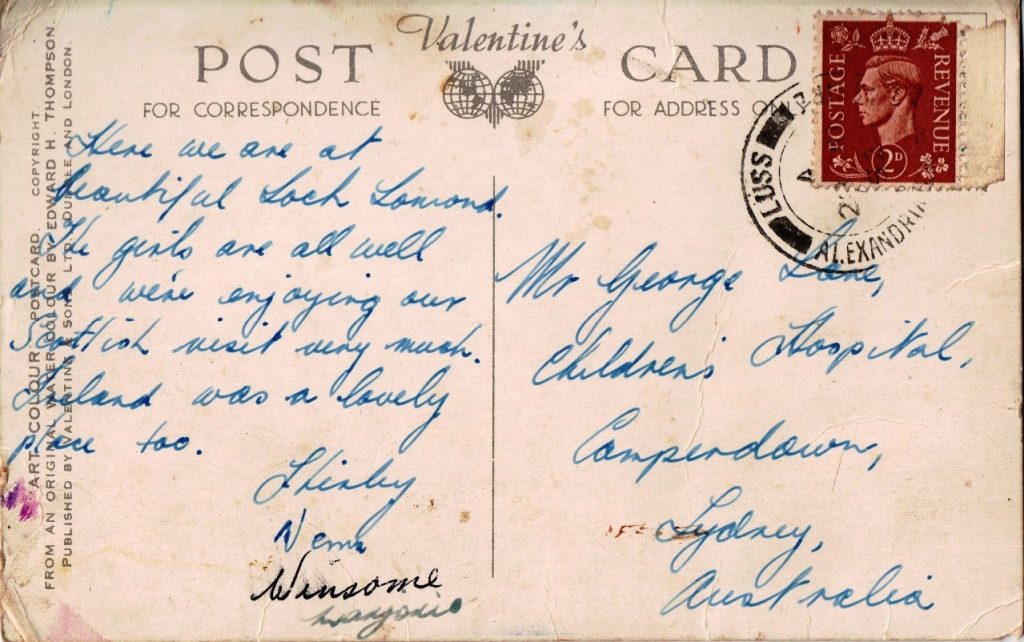

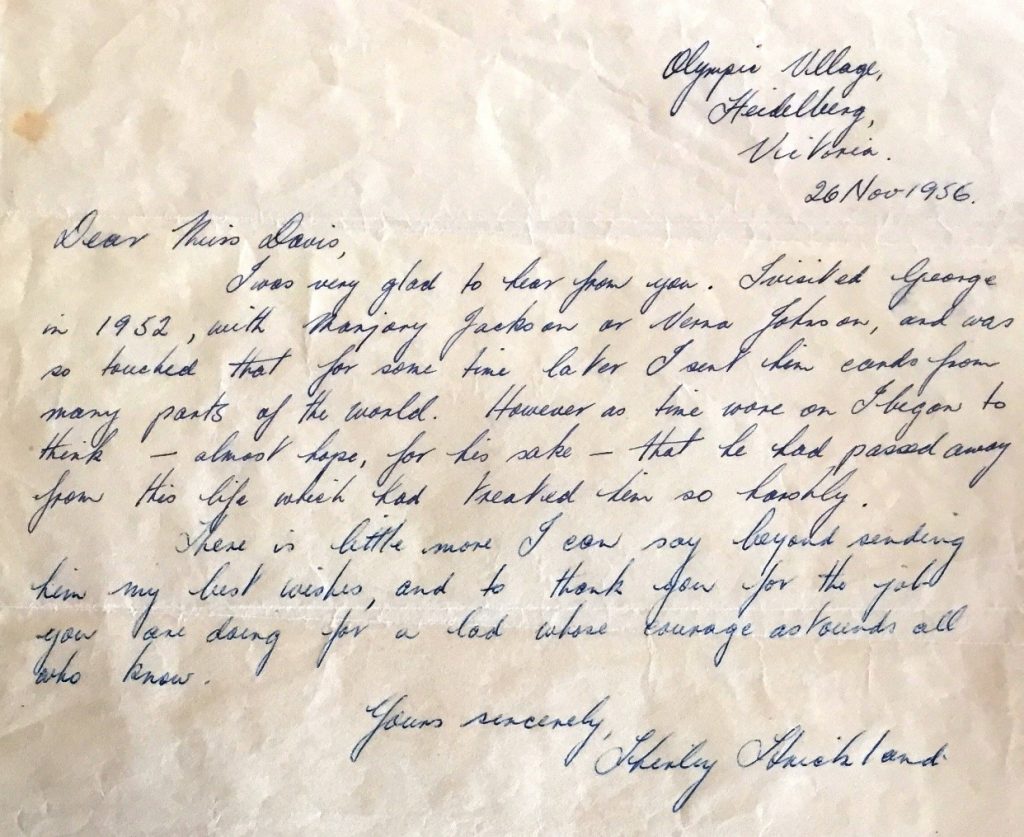

In August 1952 both the Sunday Telegraph and the Windsor and Richmond Gazette (front page) had a photograph of Marjorie Jackson visiting George. She was accompanied by Shirley Strickland and their visit to George was one of their first acts after returning from the 1952 Helsinki Games. While away the girls had sent George the following postcard.

At Helsinki Marjorie had won gold medals in both 100 (equalling world record) and 200 metres (breaking the world record). Marjorie Jackson was the first Australian female runner to break a world record. Marjorie became known as the “Lithgow Flash”. In January 1950 she had set the first of her ten world records and later that year gained the first of her seven Commonwealth Games Gold Medals. In London in 1948 Shirley Strickland had come 3rd in the 80 and 100 metre hurdles and won silver in the 4 x 100 metre relay. In Helsinki she won the 80 metre hurdles in record time and won bronze in the 100. In 1956 at Melbourne Olympics she won the 80 metre hurdles and the 4×100 relay. Her statue stands outside Melbourne Cricket Ground. She won more Olympic medals than any other Australian in running sports. Shirley continued to send George postcards from all parts of the world.

Probably George’s closest celebrity friend and particular idol was boxer Jimmy Carruthers, who, in his ninth professional fight, in 1951, won the Australian Bantamweight title. In his fifteenth fight, in 1952, in Johannesburg, South Africa he beat Vic Toweel, knocking him out in two minutes and nineteen seconds to become World Bantamweight Champion. Jimmy had visited George for his birthday on 7 July. Jimmy and his Manager, Bill McConnell, had both written to George from South Africa and Jimmy had told George he would come to see him as soon as he got back. On the night of the fight static prevented George from hearing the broadcast but, by 6am, he knew the result and awakened the ward with his jubilant shouting. George commented, “It will be the happiest day of my life – fancy having a world champion coming to visit me. I knew he would win because he said in his letters he was going to.”

shows the affect that the arthritis had on George in the swelling of his fingers.

Another visitor to George was Melbourne Cup winner “Dalray’s” owner , Mr. Neville, who brought the Melbourne Cup to the hospital to show George. A footnote to this particular article told that George had backed “Reformed” each way in the Cup, all up “Jimmy Carruthers”, and won £9.

George received, in December 1952 a letter from Radio 2UE legend Howard Craven, who wrote, “ I suppose you are wondering why I have been asking Teenagers of the Night to get in touch with us. Well, the idea is, we are going to record a special “Rumpus Room” Programme for Christmas Day and we are inviting as many “Teenagers of the Night” as we can find to form the audience when we record the show next Tuesday night. Of course, we realise, George, that you will not be able to come to the recording but we do hope that you will be able to hear the show between five and six o’clock on Christmas evening. You will be our special “Teenager of the Night” during the show”.

Letters from Fred Hoy a Gallipoli Veteran

December 1952 proved a busy month for George. Sent from Cremorne on 22nd was another letter from Fred Hoy (the first of three letters sent to George, one in March 1953, the other in July 1957). We are unsure who he was but his first letter reveals he fought at Gallipoli and took part in the evacuation on 20 December, going to Lemnos Island from whence they sailed in a transport ship through the Aegean Sea to Egypt. Xmas Day in the Aegean Sea was spent “looking out for submarines” and being a bit disappointed that they did not see one, “just out of curiosity”. The Real Xmas dinner they had been anticipating proved a disappointment, the pudding was so water-logged they could not eat it and the C.O. allowed one bottle of beer between three men. Fred’s two mates were delighted that he didn’t drink! Fred spent 10 months fighting in the Sinai Desert and his next Xmas Day was spent near the Suez Canal. They were actually 12 miles east of the canal but, because the water in the canal was so much lower than the banks, no water was visible, so it looked as if the ships were sailing on sand.

Fred tells the next story so well that I will let him tell it again, “On Xmas Day we had a football match in the afternoon. The Headquarters’ Team played a combined team from A, B and C Squadrons, and, as I was Regimental Sarg. Major, nothing would do but I kick off officially. We had no guernseys, so played in our khaki shorts, and, as the sand was so soft that we sank to our ankles walking on it, we played in bare feet. Anyway, when the whistle blew I ran and put all I knew into that kick off, only to tumble head over heels, with, I thought, every bone in my foot broken. Some Wag(?) had substituted a case filled with sand for the real ball, much to the delight and amusement of the spectators, the rest of the troops. So that was one way of getting back on the Sarg. Major. Anyway we had a good game and a real happy time”.

Fred must have been severely wounded because he goes on to talk of his 1917 Xmas spent in Prince of Wales Hospital where he was paralysed and could not even use his hands. He was to spend his next five Christmas’s there. This probably explains why Fred and George became such good friends. Fred thanks George for the help George has given him since they got to know each other through their letters. In Fred’s words “There have been times, and will be in the future, when things go wrong and I feel like kicking over the traces, and perhaps growling a bit. Then I think of your courage and cheerfulness, George, and I feel a bit of a heel. Anyway, after meeting you personally yesterday, I promise to be good from now on.” Earlier in his letter Fred mentions walking with crutches. He also commented on meeting Mavis and Sam on his way into the ward, “They are the kind of people, who make one feel they have been friends for years and I am looking forward to seeing them again soon”. He did.

Adapting to Hearing Loss and Blindness

When he was older George was moved to his own room where he had a special bed which allowed him to be turned easily and where weekday visits were allowed. George lost his sight and later his hearing (1954 or 55?) but before he lost his hearing he had learned Braille. Therapists gave him lessons whereby they and the family could communicate by writing on his hand or chest. His mother read books to him this way. One of those books was “Reach for the Sky” the story of Douglas Bader. George had always said he didn’t want to be an “ignorant teenager” so Mavis took in newspaper cuttings to read to him on her visits

The writer of the above article tells, “At George’s hospital bed I wrote on his chest with a finger, “How did you learn Braille?” He said: “Stewart Carey from the Blind Institute came to the hospital to teach me. It took about five to six weeks to learn all the signs and so forth. Then I was able to start reading short stories and articles. For a start it took me a fair while to read a page of Braille. … I started reading my first book in October.” Because Braille books were too heavy the Blind Society would send George the loose sheets before they were bound into a book. George repayed the Blind Society by proofreading the books. Sam, George’s father had a friend make a special stand to hold the Braille sheets. As George finished reading a sheet a nurse would replace it with the next sheet.

Ward Sister Robin Edman spent many countless hours “finger talking” to George. She commented George had one of the most active minds in the ward and could tell you anything about the hospital news. “Nurses, sisters and doctors all make a point of writing a few words on his chest whenever they go past. They’re always met with questions, questions, questions and more questions. He wants to know all the local news – sport, weather, events of the day, and about other young people. Twice a week his mother finger-writes onto his chest events he’s interested in from the newspapers.” Rheumatoid Arthritis had crippled him to such an extent that he had to be spoon-fed.

More Sporting Visitors

The Daily Mirror of 8 September 1955 wrote of another of George’s idols, Rugby League star Clive Churchill, telling how George had written to him when he broke his arm, hoping he’d soon be playing again, “I took him a jersey once, and they tell me he insists on wearing it over his pyjamas every day”. The reporter continued, “Sure enough, there was the jersey, newly pressed, on George’s shoulder, ready to be turned back to leave the bare chest that is his ‘blackboard”. That jersey, seen below, is still in the possession of the Lane family and is one of Churchill’s Australian Test jumpers!

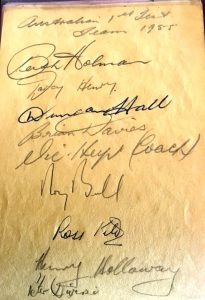

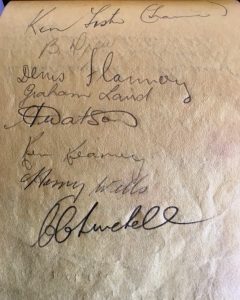

Autographs

Another treasured Lane family possession is George’s autograph book. A Daily Mirror photograph and article on 21 March 1955, tells of Clive Churchill finger talking to George – “Today Churchill discussed tomorrow’s Souths v. Parramatta match … George wished Churchill successful selection in the Australian test team for the forthcoming World Cup series”.

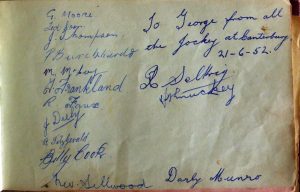

Autographs included the nurses who worked in the hospital, individuals and some sporting teams. The following page show pages signed by the 1955 Australian Rugby League team for the First Test and all the Jockeys at Canterbury Racetrack on 21 June 1952.

|

|

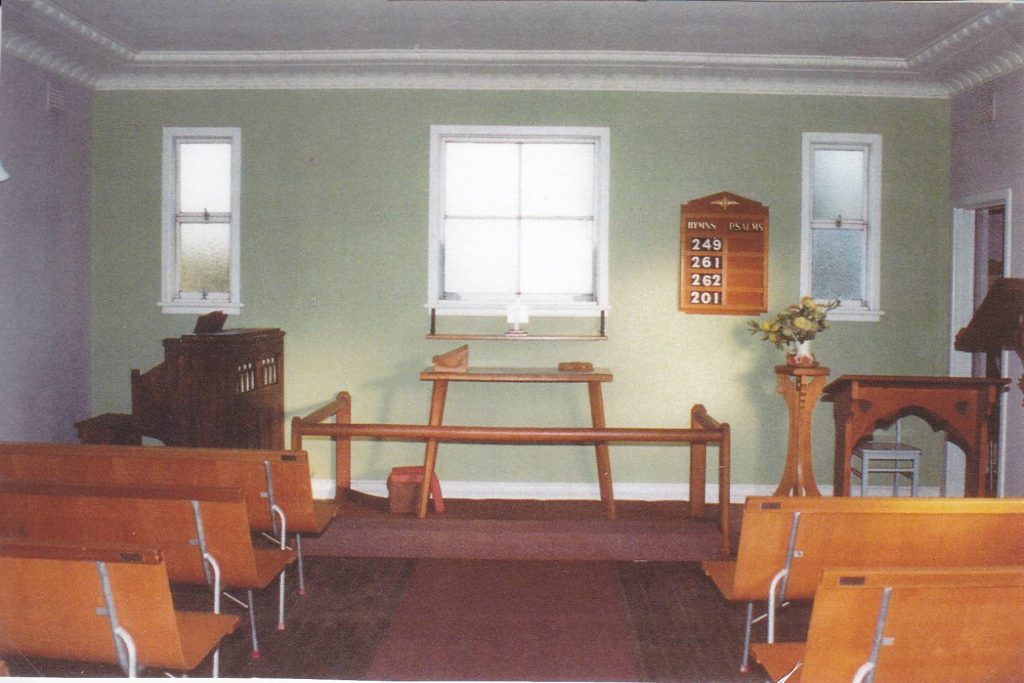

Faith

In The New Presbyterian of 29 June 1956 an article by Robert Macarthur said, “One day in May I walked into the Children’s Hospital at Camperdown with Bob Allen, of our Riverstone Church. I felt quite uneasy, because I was heading for an interview with a young patient, who is both deaf and blind. Just how to converse with such a patient had me worried”. Robert questioned Bob on why an 18 year old was still in a Children’s Hospital. Bob’s reply, “He has been here for six years … but nobody wants to see him go anywhere else.” Robert described George’s bed “- quite the oddest hospital bed I had ever seen. Indeed it was more like a long narrow traymobile, but on it lay Georgie Lane.”

Further on in the article Robert relates, “I am told that, when Ken Rosewall visited him, George knew more about the tennis stars wins than the famous Ken himself. (Ken “Muscles” Rosewall, with partner Lew Hoad, won the Men’s Doubles at Wimbledon in 1953 and 1956, plus four Australian, two French and two United States titles).… On a recent Saturday one of the Residents gave George a running description of the Queensland v. N.S.W. match.”

Robert Macarthur concluded his article of 29 June 1956 with the following, “Before leaving Georgie Lane I felt I had discovered why so many footballers, nurses, tennis stars, athletes, dancers and others make a pilgrimage to that narrow bed. It is because deep down this lad has never lost touch with the Living God”. Robert Macarthur concluded, “If only you too had known George”.

Brought up in the Presbyterian Church at Riverstone, where he was a Sunday School prize-winner, George did not speak openly of his spiritual life. Every Sunday a religious story or text was written on George’s chest. By his bedside, on a picture of a well-known footballer, was a beautifully illustrated text “Come unto me all ye that labour and are heavy laden and I will give you rest”. On 2 May of that year Prof. John McIntyre, just before he was appointed to Edinburgh University, received George into full membership of the Church, and gave him communion. George’s comment, “It is a great feeling to be one of the big family of the friends of Jesus”.

In 1962, when Dr. John McIntyre published “On the Love of God”, he spoke of two celebrations of the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper which had prompted him to write the book. One was the occasion of George’s first communion of which he wrote, “Never have I been so profoundly conscious of the encompassing cloud of witnesses or of the near Presence …Where men have said in every generation, God cannot be, there for George, God was.”

People in Office

A well-known personage to doctor George, in 1957, was Junior Medical Officer Dr. Marie Bashir, who, on 1 March 2001 become NSW’s second longest and popular Governor, serving in that role for 13 years. Dr. Bashir’s husband was Wallaby Nicholas Shehadie who brought the entire Australian Rugby Union team in to visit George before they embarked overseas. None of George’s remaining family can tell, with certainty, who prompted the other prestigious visitors who flocked to George’s bedside, or who wrote to him, but, that they did, speaks volumes for George and his personality.

In 1957 George received a reply to a letter he had dictated to Queen Elizabeth II in which he spoke of the Duke of Edinburgh’s opening of and involvement in the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne. The queen’s secretary replied, “Her Majesty was very moved by the courage and determination displayed by George Lane in his adversity, and greatly appreciated his writing to her”.

21st Celebrations

On 7 July 1957 George turned 21. Again, a letter written two days later, from Fred Hoy, one of the many who attended, gives us some insight into what a special day it must have been for George. Fred commented, “I have not seen so many people in your room before. …What a lovely party yours was? And what a lot of work your mother must have put into it. That cake looked beautiful, and I’m sure you know just what it was like. … I was sorry that I had to leave early…but I did wait until the speeches were made: and believe me, yours was excellent…you said what was in your heart, George. We could tell that as you spoke; and you said just enough and to the point. I thought that Mr. Davis spoke very nicely, in introducing you, and I felt that he was echoing all our sentiments. …You would get a thrill from knowing that Souths toppled Norths on Saturday; and you will know now, that Churchill is out of Thursday’s match owing to injuries. Bad luck.”

A delightful article in the Sunday Telegraph on 9 March 1958 tells of how a nurse had rushed to George’s bedside, two hospital blocks from the road, less than five minutes after the Queen Mother’s visit and, in letters three inches high, had written on George’s chest “Queen Mother looking beautiful stopped her car outside front gate…Little girl patient curtsied and gave her a bunch of flowers.” George replied in a well-modulated voice, “I’m glad she looked beautiful for the other kids.”

Moving

In 1958 the Army was called out to Camperdown to move George to his new home “Weemala” at Royal Ryde Homes for Incurables. Hospital authorities had called on the Army because George’s special bed would not fit in an ambulance. George had been 11 when he entered the Children’s Hospital with chronic rheumatoid arthritis which had slowly withered his limbs. George lost his sight and hearing but “never his courage”. George was the oldest patient at the hospital. Because he was a special case the hospital had “waived” its 14 years age limit. In the ten years George had been there he had won the hearts of the nursing staff who called him “Smiler” because he was always laughing and never complained.” Doctors and nurses crowded around George’s bed to trace the word “goodbye” on his hand. George smiled, thanked them, and apologised for being a bother.

Mavis and Sam rode with George in the truck. At “Weemala” Mavis “palm traced” introductions to the nursing staff and demonstrated the tracing technique to the Matron M.M. Savell who then traced out, “Hello George, I hope you will be happy here”. Mavis interpreted for a Daily Telegraph interview. George spoke the words as his mother deftly traced them on his hand. George said, “The Army truck was a bit bumpy but the soldiers did a good job.” He punctuated every sentence with a grin and said, “I am looking forward to my new life here. I felt sad leaving Camperdown Hospital. I want to thank the hospital staff for what they did for me, but anything I say will be inadequate”.

The Legacy

George passed away on 12 May 1958, aged 21. Despite being bedridden for ten years and deaf and blind for half of that time, George was a unique young man who provided inspiration to all who met him including some of the greatest sportsmen and women of the time. As Shirley Strickland wrote in 1956 “George is a lad “whose courage astounds all who know him”.

George’s Specialist doctor had been Professor Sir Lorimer Dods who also became his close friend. In September 1959, as chairman of the Children’s Medical Research Foundation, Professor Lorimer Dods, wrote to Sam and Mavis “to express my own sincere appreciation and that of our Committee for your generous help in the establishment of the Children’s Medical Research Foundation”. This organisation is still in operation today, in one way a legacy to George and his dedicated parents.