by Charley Persak

I was born Volodymyr Demeczyk on the 11th January 1943 in Dombrowa, Poland. My father Stanislaw was Polish and my mother Tatjana was Ukrainian, I was the first of their three children. My brother Josef was born in 1950 and sister Erica was born in 1955, both were born in Riverstone.

My mother’s family were quite wealthy share-farmers in the Ukraine and lived off the land, growing all their food and meat in the few short months of their summer. With no electricity or refrigerators they used to bury their food in the snow and use it as required through the long winters.

When the Russians invaded Ukraine they confiscated all their land and farms; my mother aged 18 fled to Poland where she met and married Stanislaw. The family were to experience all the horrors of World War 2. I recall my mother saying when I was born she was afraid to put me down, she carried me everywhere for the first two years of my life. It was sad, but people losing their babies would actually steal other people’s babies and children to replace their lost ones.

Barely three years old at the time, I still have memories of the bombs dropping, the blackouts, the snow drifts, and the day I got lost in the snow. I recall the day the Americans made us drop everything and rushed everybody outside from their buildings, prior to the area being bombed.

I remember the day I found all this paper money in a garbage bin; money in times of war becomes valueless, but I didn’t realise this at the time. Leaning into the bin to get the money for my mother I fell in, dad found me with my feet sticking out and very grubby from the garbage. I got into big trouble that day as I had just had a bath and was dressed in my good clothes. It was a lot of work keeping a kid clean in those days, there was no running hot water and the water had to be boiled in a kettle; you washed in a round tub on the floor with an inch or two of water, no matter how cold the weather was.

Another time I was sent to get some rations from the store and took so long my father came looking for me. He found me waiting to cross the road, watching a huge convoy of American Army trucks and tanks come rolling into town, a show of might so big it seemed to take ages to pass.

As the war ended our family was sent to a refugee camp for an unknown period – maybe a year or two, while awaiting transport to Australia or Canada.

I became very sick in Naples and for a time it was thought I would be unable to travel with my parents. Mother put hot poultices on my chest and nursed me day and night back to good health. The problem had been caused by eating too many tomatoes and peanuts, produce that I had never seen before in my life until I came to Italy.

Dad chose Australia and we sailed from Naples in July 1949 on the converted American troopship, ‘General W. M. Black.’ As with other migrant ships, the men and women lived in different parts of the ship. As the youngest child on the ship I felt I had the run of the ship, the crew spoiling me with a never ending supply of chocolates and ice-cream. The family arrived in Australia on the 29th November, 1949.

We disembarked in Sydney and were transferred by bus to the migrant camp at Parkes in western NSW which had been an Army camp during the war. We were housed in what they called ‘Nissan Huts’, big round topped buildings about 100 feet long and capable of holding lots of families. My father was given a job on the railways so we returned to Sydney and lived in tents located adjacent to the railway yards at Clyde. My father had money deducted from his wages to pay back the cost of bringing our family out from Europe (unlike today).

When Dad had saved enough money he bought a small block of land in Creek Street, Riverstone and began building a shack made of wooden shipping cases. The wooden cases were bought from Knight’s Garage and had been used to bring cars into Australia from overseas. We lived in this shack until Dad bought another house on the opposite side of Creek Street. Dad left the railways after a few years and got a job at Max Gosden’s saw mill in Edward Street, where he worked till he retired.

I was now seven, could speak German, Polish and Ukrainian, and had to start school to learn English. My Mum changed my name to Arnold Persak, because it was easier for the teachers and children to remember and might help me integrate more quickly. I went to the Catholic Primary School in Riverstone and with no knowledge of English found it very difficult at first. One day I walked all the way home (two kilometres) in the middle of lessons to go to the toilet, because no one had told me there were toilets at the school. When I had learnt a little English I did better at school and got quite good grades, especially for neat work.

At about age eight my school had a baptism day and they asked me if I had been baptised; I said no, so they baptised me. The priest asked me my name; I had a best friend called Charley so I told the priest my name was Charley. And that is what my mother, father and everyone called me from that day on. Though my mother’s pet name for me became ‘Chalka’.

Growing up in Riverstone was great; it was a small country town on the outskirts of Sydney and we still had dirt streets. A railway line ran through the town and steam trains, both passenger and stock trains, were a common sight. At the railway gates there was a big water tank about 30 feet in the air on a stand so the trains could pull under and fill up with water to make the steam. There was a meatworks and a textile factory in town and they employed most of the townsfolk. I used to walk while I was at primary school and later at high school in Richmond I had to take the steam train.

We had to bathe twice a week in a tin tub on the floor with the water heated on two primus stoves. At times I remember Mum taking the clothes to the creek to wash them. The creek often flooded, in 1956 there was over four feet of water in our house and we were billeted in the Masonic Hall in Garfield Road, now used as the Museum.

I was expected to do lots of chores around the house even when I was quite young. We had a huge vegie garden where Mum grew most of our food, my job was to help weed and chip it. We had a jersey cow and we all just loved the still warm fresh milk, Mum made all our butter and cheese. Once when I was age eight and my Mum was in hospital having my little brother Josef, it was my job to milk the cow. The cow didn’t really know me, and no matter how hard I tried I couldn’t catch her. So I went inside and got one of mum’s dresses and put it on. I walked back down the paddock with my bucket, and the cow just stood there and let me milk her.

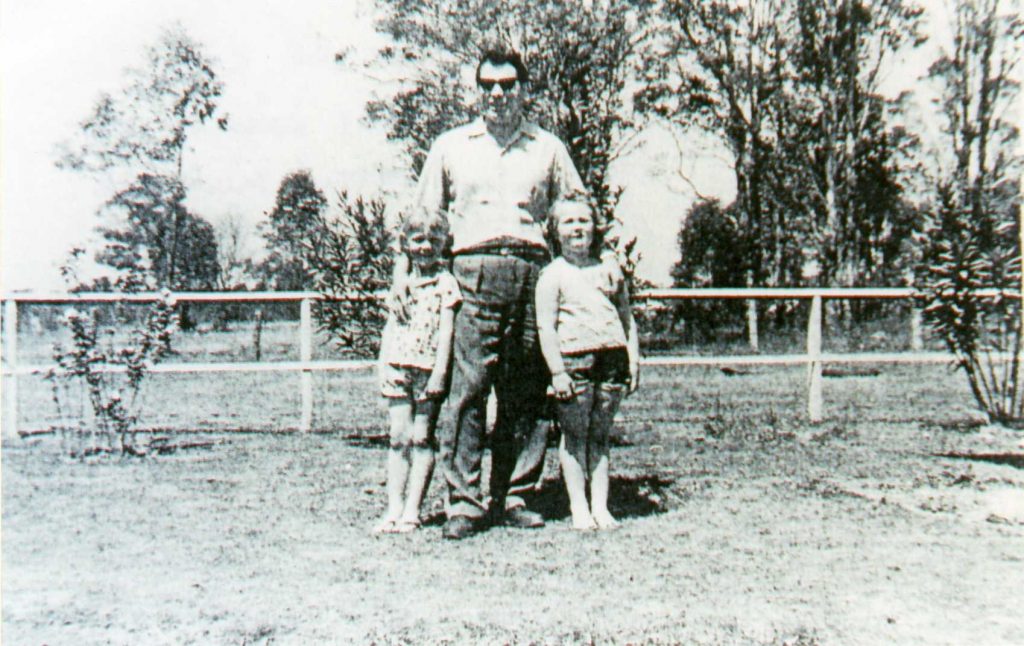

Photo: Charlie Persak Collection

We, my friends and I, used to play around in the creek down the back of our house. We would swim, build cubby houses and swing out of the trees on a rope and fall into the water. We spent all our time outside, I don’t think we ever wore shoes. There was no television in Australia in those days. My friends used to ask me to ask my Mum to make us ‘platzky’ or ‘pirogi’. ‘Platzky’ are either potato pancakes or flour pancakes. ‘Pirogi’ are little pillows of dough filled with mashed potatoes and cheese and fried with butter and onions. Delicious!!!.

Mum would cook for a week just before Easter and we would go to church on Good Friday. On Saturday Mum would spend all day in the kitchen again cooking. We had schnitzels, we had sauerkraut, potatoes, pirogi, platzky, mushroom sauces and trifles. We had bowls of everything and we would take it to church on Saturday night to be blessed. Sunday was the day for the feasts of all feasts, family and friends would all get together to eat and eat. There were a lot of European families in Riverstone and it was a lovely community spirit. We never had any chocolate or candy Easter eggs. It was more traditional for Europeans to paint pretty pictures and patterns on boiled eggs for the children, so that’s what we got. Plus the feast of course, which was most important.

Christmas was another fun time for all the families to get together to eat and meet; it was the same then. Mum would cook for days and we would eat it all in one day. We didn’t get any Christmas presents either, as most of the money went towards food and education for us. Although I do remember when I was 12 getting a push bike for Christmas, but as it turned out I could only ride it on weekends because Dad rode it to work every week day. We didn’t really mind though, because we always had a full tummy and a warm bed.

Some days after school I recall playing near the station and receiving a shilling to run down to open and close the railway gates. When Mr Murray owned the Olympia theatre I would chip and clear away the weeds behind the theatre and the meeting room, just to get free admission to the Saturday afternoon pictures. To get pocket money as a lad I remember helping deliver bottles of Noon’s soft drinks, also getting up early to help the iceman with his deliveries to the homes in our area. I recall the day the Vocational Guidance Officer came to the school and really put me down when he suggested I was more suited to being a garbage collector than a mechanic.

Although most of the old people have passed on, lots of their children and grandchildren still live in the area. We don’t have the big celebrations that we used to but when we get together, we still have a lot of fun and good memories. The spirit is still there.

I left school when I was 15 and worked as an offsider on one of A J Bush’s bone trucks before getting a job in the Textile plant where I worked for seven years until it closed. My next job was with Parramatta Spare parts in their wrecking yard.

I decided the spare parts business was the way to go, so started buying in spare parts and storing them in a wardrobe in a chook shed in our backyard. I then went into business at the Creek Street address, the year was 1967.Some of my first customers were the Riverstone footballers who on training nights would leave their cars with me to change tyres or carry out repairs.

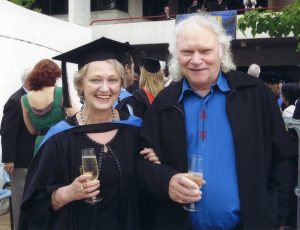

Photo: Erica Persak