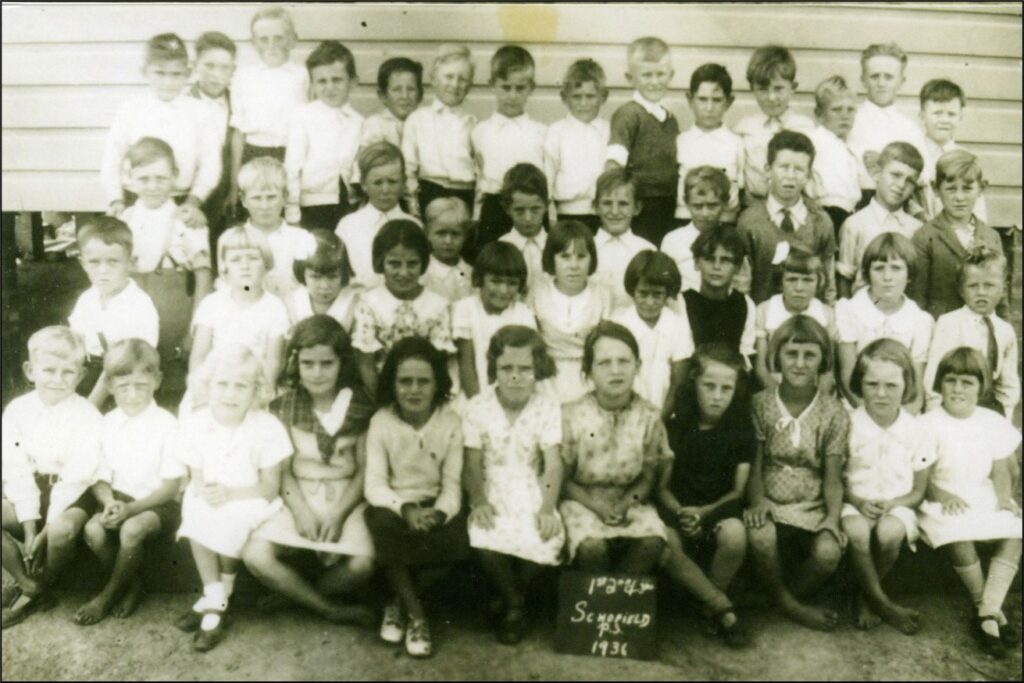

by Nell Moody

For three years, from the beginning of 1940 to the end of 1942, Miss Roston’s and then Miss King’s classroom at Schofields Public School, was at the centre of my life.

We sat in double wooden desks with seats that folded down from the desk behind. I sat with my friend Ann who also lived in Schofields Farm Road.

There was another classroom, but that was for the big boys and girls, who were taught by Mr Middleton, the headmaster.

A long veranda outside the two rooms had a bell fixed to its end, which was rung by a boy from Mr Middleton’s class, to signal the start and end of lessons. At the other end of the building was a row of basins and a bubbler. The boys and girls toilets were some distance behind the building and each had an entry of corrugated iron.

Ann and I sat in the far back seat of our classroom, probably because we were both very quiet.

I remember only brief talking by our teacher and some chanting of “times tables”. My most vivid memory is of silent reading. When we finished our set work, we were allowed to go to the book cupboard, out the front of the room, and get a school magazine.

Miss King was a very busy lady. The room was full, with three classes and over forty pupils. I am sure she allocated her time well and Ann and I enjoyed the magazines.

Today’s pupil-teacher ratio is much smaller. The Second World War was on then and many teachers were in the Armed Services, so large classes were common.

When the bell rang for playtime or lunchtime we seemed to be really free. To my knowledge no one checked whether we were eating or playing, or where we were. I particularly remember our “cubby house”, which was just a space under a tree with a hanging branch. For five or six little girls it was “ours”. Boys occupied nearly all the front of the school playgrounds, pushing and shoving, and the girls found places on the edges. Some of the big pupils played more organised games behind the school. Mr Middleton and Miss King just seemed to appear from time to time.

One day some boys tied the long paspalum grass heads together to trip unwary people. One such person was Mr Middleton who I think, was pursuing a naughty boy at the time. I was “that girl laughing” who was sent up to the veranda to wait for Mr Middleton to get his cane and then I had to put my hand out. I probably only got a ‘tap’ for effect. I didn’t cry, but I didn’t tell my parents either, and I never got the cane again. I don’t remember the cane ever being used by Miss King or Miss Roston.

A particularly naughty boy in my class brought a big knife to school. He said he would cut off my head. He must have made similar threats to others, because Mr Middleton put him in the book cupboard. I worried that he would tear those precious magazines, but he was soon released.

One day my cousin Ian, who was also in my class, was told by Miss King to empty his pockets out onto the desk. His pockets must have been bulging, because I remember a sling-shot (a short forked stick with a rubber band attached), a number of large pebbles and a large piece of torn sheet which contained two carefully wrapped bird’s eggs. Miss King said how cruel it was to steal eggs from a mother bird, and how these eggs would now never hatch. Conservation was in its infancy in the 1940’s.

Miss King then asked Ian where his shoes were. I wondered how she knew that he left them in a tree and collected them on the way home. Boys in my class liked to be barefoot. I think they would be thought tough.

School uniforms were rare at Schofields, only a few girls wore tunics, most wore anything they had. Leather shoes were rare, sandshoes common and many boys regarded all shoes as “sissy”. The word “sissy” was a common insult.

Some girls came to school in pretty frocks with lace around the bottom. I envied them. Years later I realised that the lace was added to make the dress last another season. Clothing coupons had been introduced during the war and children who grew out of their clothes could be a problem. “Hand-me-downs” were what most children had and no girl had more than one good dress.

Many boys wore braces. They could put their thumbs under them and make them “snap”. The braces were considered “MANLY” and “GROWN UP”.

There was no tuck shop or canteen. We brought our own food, usually wrapped in greaseproof paper or a serviette or even newspaper.

My father always cut my lunch. He cut thick slices of bread with a bread knife. Sliced, soft bread was far in the future. On Monday meat filling from the left over Sunday roast was common and for the rest of the week peanut butter, Marmite or plum jam featured. Not every child had fresh fruit. Modern children would be appalled at our lunches but we ate what was in front of us. Complaining abut food was pointless, because one was immediately told that some children in other countries were starving and that it was better than bread and dripping which was what our parents said they had as children. Attention to a balanced diet was years away as was plastic wrap and lunch boxes. I do remember talk about Oslo lunch and salad sandwiches, I think after the war.

The 1939-1945 war was well known to us, because our families talked about it a lot. Trenches were dug in the school grounds. No doubt the new air base that was built on what we called Pye’s paddocks on the Quakers Hill side of the Schofields, the Richmond Aerodrome, and the increasing number of planes overhead made the trenches a sensible precaution.

We were not allowed to play in the trenches but were taken into them for a drill which involved a lot of crouching down and biting down on a wooden “dolly peg”. Our mothers had to make us a bag for this peg to hang around our necks. I think it also contained some rag or cotton wool to stuff in our ears. This was, I guess, to cushion the noise of falling bombs and the peg to stop us biting our tongues. My mother had torn up an old sheet for mine. Thankfully no bombs fell and eventually the trenches filled with water and were filled in.

Schofields Public School was a world to itself. I do not remember even having a visit from another school or being taken outside of its grounds in school time. There were no excursions and sports equipment was very limited. I do not remember visiting speakers or scripture teachers or music or art or radio. There were certainly no parent-teacher nights or even a phone for parents to ring the school on . It was unusual for a parent to even visit the school except to call to leave or collect us.

Maybe present day children would think we were deprived, but we did not regard ourselves so.

For me Schofields Public School was a happy experience. There was no homework and little boredom. Though our parents worried about the war and their friends and relatives who served in it, it was far, far away from us children.

We may have had a lot less in the way of possessions than today’s children, but we didn’t know that Australia would change or that other places were different. For us, our world was Schofields and we liked it just as it was.