by Chris Counter

The Battle of Vinegar Hill Re-enactment at Rouse Hill was a significant cultural event in 2004. This is the experience of Chris Counter who started out with only a general interest in the subject but unexpectedly finished up reliving the history of those days in March 1804.

Courtesy of my employer Sell & Parker Pty Ltd, I attended a fundraising luncheon at Parliament House on 16th July 2003, for Blacktown City Labor Councillors. Councillor Alan Pendleton, Mayor of Blacktown City gave an address in which he spoke of the forthcoming commemoration of the 200th Anniversary of the Battle of Vinegar Hill. Having an interest in local history, I was immediately excited by the prospect of a local celebration.

Following mounting publicity about the event I decided on the 21st February this year to contact Historica Pty Ltd, the organizers of the re-enactment, to offer any last minute assistance on the weekend of the celebration, with the rider that I was prepared to do anything to help. (To be honest I was thinking of some sort of administration work).

As advised by Historica, I completed a participant application form and returned it by the cut off date of 27th February, ticking off in the appropriate box my availability to help at all events. On Monday 1st March, I received an e-mail asking if I would like to participate in a group re-tracing the 30 kilometre walk of the convicts involved in the breakout from Castle Hill Government Farm to Rouse Hill (site of the Battle of Vinegar Hill), via ‘Sugar Loaf’ (Constitution) Hill in Wentworthville. I was very pleased to be asked and agreed after a 10 second consideration.

As this was to be an authentic re-enactment, guidelines were issued as to what to wear and what not to wear. I immediately began a search amongst friends for hemp rope, a wooden water bottle, a plain coloured wool blanket and an old black lantern. The costume was to be loaned by Historica.

On Tuesday 2nd March, I shaved off my moustache for only the second time in 20 years and shaped my beard in a style after Joseph Holt, an Irish leader who, whilst involved in the planning of the uprising, did not take part. My wife suggested I now looked like a leprechaun (which was not my intention).

I arrived at Rouse Hill Regional Park at 3pm on Thursday 4th March, 200 years to the day of the rebellion. We were due to leave by bus for Castle Hill Heritage Park, (the original site of the Government Farm), at 6.30pm. The time spent in between was used to sort out clothing, get dressed and into character. At 5.30pm an urgent call was received at the park from Blacktown Railway station, where a late arrival from the North coast had just arrived. He was asking for suggestions on how he could get to the park in time to catch the bus with us. With no other way of him getting to the park on time I offered to drive to Blacktown and collect him. In the last minute rush after we arrived back at the park I left my food in the car, which was to be somewhat of a relief later that night as you will read further on.

16 of us, led by Dr Stephen Gapps, arrived at Castle Hill Heritage Park at 7.30pm. As we circled the crowd on hand for the commemorative ceremony of the breakout at the Government Farm, I felt the first of what was to be many goose bump attacks. As speeches were being made by the dignitaries present we walked quietly through the crowd to the official dias where we stood for a few minutes before moving off past the archeological diggings of the convict barracks on route to Constitution Hill Reserve. Walking silently past the diggings under the full moon was a very eerie sensation.

As this was a serious re-enactment there was a reserved attitude amongst the group. Most of us were carrying a lighted lantern and a 2 metre long wooden pole, some with bayonets attached. All of us carried a bedroll over our shoulder. As we headed toward Castle Hill shopping centre the odd passing motorists gave us a wave and a toot which was encouraging.

We arrived at Constitution Hill Reserve at 11.15pm most of us tired and weary. Stephen insisted that we should immediately practice some drill then have a few drinks as had been done on the same spot 200 years before. To his commands we practiced our advancing and ordering of the Pike (our poles) until there was some form of synchronization to the movements, then we practiced marching. It was goose bump time for me as we marched in the moonlight on top of the hill, the air still and warm.

We were not permitted to light a fire. As it was a mild night we decided not to use the tents that had been dropped off at the park earlier in the day. We laid out our blankets on the grass and had a few drinks, my drink was of the roughest grog I have ever tasted. Not unlike, I would imagine, the spirits looted by the rebels on their journey in 1804. There was talk of what the rebels would have been thinking 200 years before when there was no signal fire to be seen at Parramatta. A burning Elizabeth Farm would have been clearly visible from this elevated position and given them reason to move on to Parramatta. The absence of the signal forced the change of plan to turn to the Hawkesbury, seeking supporters to join their ranks.

Food was now being shared around. Crusty bread with thick hunks of cheese and preserved meat, unwrapped from rough cloths. At that point I was glad I had left my food in the car as, forgetting to be completely authentic, my wife had wrapped my shaved turkey, camembert and sun dried tomato sandwiches in those neat zip top plastic individual sandwich bags! I did not tell the others about that.

Just before bedding down, 2 of our party decided that rather than face a night under the stars and another 15 kilometre walk at dawn, they would prefer to be picked up by their wives and taken home. There were now 14 of us left. The last attack of goose bumps for the day came as I lay looking up into the sky thinking that, whilst so much has changed in NSW over the last 200 years I was able to look up at basically the same sight seen by the insurgents in 1804.

Not long after dawn the next morning we packed up our gear, posed for some photographs for the Sydney Morning Herald, then proceeded on with our journey (having no tea, coffee or breakfast). As we neared the junction of the Windsor Road and the M2 motorway we were joined by another walker who was not able to start with us at Castle Hill the previous night. Our number was now 15. Passing motorists took a great interest in us as we walked on the side of Windsor Road. Traffic in both directions tooted their horn and waved as they passed. We were stopped by the Police as we approached the junction of Seven Hills Road. A motorist had called them to report a sighting of a “Bunch of men wearing turbans and carrying sticks with knives tied on the end”. Even though the Police had been advised of our intended route they were obliged to check out the report. They left us, chuckling to themselves.

By the time we reached the corner of Sunnyholt Road, where we stopped for refreshments, another three of our group felt they should not continue. Bleeding blisters and swollen feet might mean they would not be able to join the Battle Re-enactment on Sunday if they carried on, so a lift was provided. Our group now numbered 11.

We reached the perimeter of Castlebrook Cemetery at 11am where we rested until 11.30am, the time that the battle took place in 1804. At 11.30am we walked across the lawn and up the hill to the Battle of Vinegar Hill Monument where the Commemoration Ceremony was taking place. We arrived to cheers from other costumed re-enactors and the crowd gathered to hear an address from, among others, the Mayor of Blacktown and the Irish Consul General.

I suffered my final attack of the goose bumps on this walk as we stood for one minute silence, exactly 200 years to the day and time that the Battle of Vinegar Hill took place.

Once I had accepted the invitation to “walk the walk”, I assumed that I would not be needed to take part in the actual re-enactment of the Battle of Vinegar Hill on Sunday 7th of March. During the walk however I found out that I would be the only one of those walking not to take part in the battle, so I decided that I should join in.

I was not available to rehearse on Saturday or to see the steady stream of more than 200 enthusiastic volunteer re-enactors on both sides that came from far and wide to take part in the event. A live-in authentic camp site of more than 30 tents was being set up to demonstrate camp life in 1804.

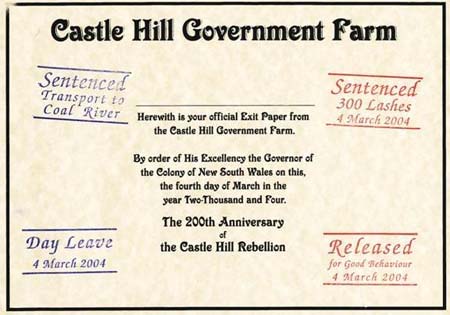

On Sunday I arrived at Rouse Hill at 8.00am. I had driven from Gladesville through pouring rain that gradually abated until I reached Rouse Hill where it had thankfully not rained at all. There was plenty of activity in the park with portable stages, stalls, seating and toilets now evident in various sections. Whilst it was overcast there was a general buzz of anticipation, dare I say excitement, among the people present. More importantly the general public was beginning to come in the gates. I was issued with a facsimile of a wax sealed copy of a pass signed by Lieut Col Paterson adjutant for Governor Phillip Gidley King. This security pass was to be used for coming in and out of the camp which was closed to the general public but on view to them from all sides.

By 10.30am we were practicing drill, I had been seconded to the 2nd division of pike, a group of about 50. Following drill practice a group of Irishmen from Wexford in Ireland joined our ranks. The Irish accents in the ranks seemed to add greater authenticity to the cause though “Billy”, standing next to me dressed in a crisp white shirt, nicely pressed dark waistcoat and trousers, Nike sandals and socks, looked slightly out of place.

There was no doubting his enthusiasm for the event however which was infectious to those surrounding him. He tried to explain to me the Irish meaning of the word “vinegar” which apparently has a different meaning to that known to us. His soft voice, a quick rain shower and the growing din of those around us, prevented me from clearly hearing his explanation.

At 11.30am we were due to start the re-enactment but as so many people were still moving into the park and toward the viewing area, we were delayed. The atmosphere was tense. Calls of Death to the Lobsters, (a term used in the 1800’s for the red coated troops of the NSW Corps), rang loud as did insults back from the troops to the croppies. By the time we moved off in formation to the area where the re-enactment was to take place we looked and sounded to be a rowdy angry mob. “Death or liberty” was the catch cry.

The crowd cheered their encouragement as we came into view which predictably lifted even higher the spirits of all taking part. During the extremely noisy and smokey battle those chosen to die, be wounded or run away, did so on cue until the battle ended.

Those chosen to die stayed where they fell until after the battle, at which time they were retrieved by a descendant of one of the original participants in the battle in 1804. I found this to be a particularly moving end to the re-enactment.

At the end of the day Historica Pty Ltd presented us with a “Kings Shilling” as payment for the days work in the re-enactment.

So what is the legacy of this re-enactment and the cultural events leading up to it? It has highlighted to the people of NSW, more importantly the people of Western Sydney, the significance of this incident that has for so long been ignored. A false sense of history has been created through lack of education relating to the uprising, its causes and its consequences. This commemoration will surely correct that by encouraging more debate and research on the subject.