Ron Mason

My uncle, Brian Mason, had a potent memory of the early days of World War 1. It was of the day the army recruiting officers arrived at Riverstone. As a schoolboy of 9 or 10 years of age, it made a lasting impression on him. He recalled how the Army recruiters arrived on horse-back from Windsor. They were beating a drum and leading a riderless horse. They then addressed the townspeople from the verandah of the Royal Hotel issuing a challenge to the young men to take up the reins of the horse that they had been leading and to join the war effort. 1

Similar “Recruiting Meetings” were held all across the country and many young men enthusiastically volunteered to fight for the King and Mother England and of course to take part in what they thought would be a great adventure. Although Australia had a population of only about 5 million, not a great deal more than the current population of Sydney, 416,809 enlisted. Nearly 40% of these recruits came from NSW. This was significantly greater in both real terms and as a proportion of the population than any other state.

Although only a country village Riverstone, and the even smaller surrounding communities of Schofields, Marsden Park, Vineyard, Rouse Hill, Box Hill and Nelson all did their bit. Between 130 and 180 men volunteered – it is difficult to be more precise than this because of the arbitrary boundaries of the Riverstone district and the number of casual workers who, although living at Riverstone, enlisted at their home towns 2.

The first to enlist from the district was Private Fred Clark, a mutton butcher at the Meatworks and a veteran of the Boer War. 3 Clark enlisted seven days after war was declared and a few days before another local – Private Herb Davis [For more information about Davis see: “Herbert Davis – An Original Anzac”, 2005 Journal]. A week later, Clark embarked on the troopship Berrima as part of a 1,600 strong combined Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force identified as the “Tropical Unit”. 4 The exploits of this unit are not well known but they were to engage in the first Australian land operations of the war – not in the Dardanelles but much earlier and closer to home.

On the 7th August 1914 the British War Office requested that Australia seize the German colonies of Nauru, the Caroline Islands and New Guinea 5. The primary reason for this was to prevent enemy wireless stations from passing information to the German East Asiatic Squadron, commanded by Admiral Graf von Spee. This attack resulted in Australia’s first combat casualties – four sailors of a landing force and an attached Army doctor. However, unlike subsequent campaigns it was an overwhelming success, with the Unit rapidly achieving all the objectives set by the War Office.

Clark’s departure was so sudden that he left without ceremony or fanfare. This is in marked contrast to later farewells which were occasions for much speech making and celebration. [For more information see: “Riverstone in the Great War”, 2004 Journal].

Although the men who subsequently volunteered expected to be sent to Britain and then the Western Front, most were sent to Egypt to counter the threat posed by Turkey to British interests in the Middle East and to the Suez Canal. More surprising for them, although by no means a secret for even the Turkish Army leaders knew, was that after four and a half months of training near Cairo, the Australians were dispatched to the Gallipoli peninsula. The purpose of this was to facilitate a British naval operation which aimed to gain control of the Dardanelles Strait and to threaten the Turkish capital of Constantinople. 6

The story of the Australians’ landing at ANZAC Cove on 25 April 1915, and the subsequent campaign is well known. However, what is less well known is that there were at least seven and possibly eight Riverstone recruits at Gallipoli and that one – Private Archibald Robert Showers died there. The seven Riverstone recruits who fought at Gallipoli were:

-

- Private Jack Kenny, 17th Infantry Battalion

- Trooper Bert Kenny, 7th Light Horse Regiment

- Trooper Frank White, 7th Light Horse Regiment

- Trooper Austin Smith, 12th Light Horse Regiment

- Driver Bert Davis, 1st Division Trench Mortar Battery

- Private Archibald Showers, 2nd Infantry Battalion.

It is also possible that Fred Clark fought at Gallipoli. At the end of his term with the “Tropical Unit” he re-enlisted and was posted to the 18th Battalion – one of the units that was deployed to Gallipoli.

With the exception of Bert Davis, all of the Riverstone recruits were wounded during their time at Gallipoli. However, Private Showers was the only one to die. He joined the 2nd Battalion at Gallipoli on the 6th August and was reported missing on the same day. His body was never recovered but it is believed that he is buried at Lone Pine where his name is recorded on the memorial 7. All that he left behind was a hairbrush, a testament, hymn book and a match box – a sad manifest and cold comfort for his loved ones.

Letters, almost always written in indelible pencil, were tangible links between the Anzacs and home. Many of these letters were published in the Windsor and Richmond Gazette and provide an intimate insight into the happenings and attitudes of the men. One account written by Private Jack Kenny after he was invalided home from Gallipoli gives an insightful account of his time at Gallipoli:

“We left Sydney early in May of last year, making a straight run to Colombo, where we had a route march, and were much impressed by the wealthy and prosperous appearance of this port. We arrived at Port Suez about the middle of June. We disembarked there, and were taken by rail to Heliopolis, which is one of the suburbs of Cairo. After a couple of months hard training there, we left on the 15th August for Alexandria, sailing the following day for Gallipoli. It was only on the day previous that the British troopship ‘Royal Prince Edward’, was torpedoed a few hundred miles out from Alexandria, and we saw the survivors arrive in port.

Every precaution was taken to ensure a safe voyage. We had a strong escort, but I think all were pleased when we reached Lemnos Island on 18th August. We had been sleeping in life belts on deck beside our respective lifeboats. We transhipped into smaller transports on the 19th, and at midnight were anchored off Anzac. During the short run from Lemnos to Anzac we were issued with the regulation [iron] ration [48 hours supply] ammunition and water. I think our full equipment weighted nearly 100 pounds. Landing the troops took time, and it was after daylight when my turn came to get into one of the small boats which ran us into shore.

We were noticed by the Turks, with the result that one of their batteries, of which the well known gun ‘Beachy Bill’ was a member, sent a few shrapnel shells over, but, except to add to our nervousness, which we already felt, and wounding a few men, they did practically no damage. It did not take us long to scramble ashore, and once our feet were on firm ground we felt more confident. Few of us will ever forget how weird everything seemed as we neared Anzac. The great flashes of the fleets guns and the terrible explosion on the side of Achi Baba and Gaba Tepe as we passed, and the tremendous amount of rifle fire and the popping of grenades sounded very weird and horrible.

When ashore, as soon as we were allowed to rest, we went sight-seeing through the different parts of the firing-line above the beach at Anzac. I think all were very disappointed at not being able to see the enemy, though at times we were only 50 yards from their trenches. I saw a good many of their dead lying on the ‘No man’s land’ in front of the trenches occupied by the 8th Light Horse, the result of an attack made a week before.

During our first fortnight in Gallipoli we supported and relieved units at various points of the line to the east of Suvla Bay. It was pleasing to realise that our arrival enabled those of the first division to get a much needed rest from the firing-line. It was in the early morning of the 23rd August at about 2 o’clock, that I received a slight wound in the left foot from a spent bullet. After a day’s rest I was able to go about my duties again. At the beginning of September we took over Quinn’s Post from the Queenslanders. Here we were fairly comfortable under Major C. R. A. Pye, of Windsor, who was much liked by everyone.

The trenches on Quinn’s Post were very close, the widest part being 20 yards, and for a good part not more than 27 feet separated us from the Turks. Needless to say one hardly dared to show even a finger above the parapet, or he would lose it. All firing was done through an aperture in armour plates, and one could only fire at the loopholes opposite in the hope of catching a Turk looking out, and we never knew whether we hit anyone or not. Where trenches were so close hand grenades are largely used by both sides, and as one never knows where the grenades are going to land, we had to be continually on the alert, as there is not much time to get out of the way when one does succeed in getting into our trench. It is customary in such cases, if time permits, to throw a blanket or coat over the grenade, and lay flat on the ground, trusting to luck, but the explosion causes a great rush of air into the lungs of those around, frequently bringing on haemorrhage of the lungs.

While in Gallipoli I saw several charges, though I took part in none. I was much surprised at the work of the fleet. The accurate marksmanship of the gunners is wonderful, almost unnatural. On several occasions there were bombardments of the Turkish positions in front of us, and during these bouts the noise is tremendous. The vibrations of the earth greatly resembled a violent earth tremor. Throughout the latter part of September the fleet and shore batteries kept up an incessant bombardment of Achi Baba, To us, as spectators, it seemed marvellous that the very hill itself did not crumble away – yet the Turkish guns replied as gaily as ever.

At night the whole of the slopes of this hill were lit up with bursting shells, which were of different calibre, up to the 15 inch shell. Aeroplanes were largely used on both sides. On one occasion a Taube dropped a bomb rather close to us, but it burst without doing any damage or injuring anyone. Some of the aeroplanes are fitted with machine guns. It sounds peculiar to hear these rattling among the clouds. In modern warfare danger not only lies on all sides, but above and below. In many places the trenches were being undermined the whole time, and one never knows at what moment the whole trench formation, with men and everything else, will go upwards in pieces.

While in Gallipoli I saw Sgt. Eric Pye of the A. M. C., and Privates Walker and Bell, all of Windsor. They were in fairly good health at the time of my leaving [Oct 2nd] but a good deal battle-worn. Owing to illness, I was obliged to leave Anzac on 2nd October and did not return before the evacuation. Trooper Frank White and my brother Bert, landed a few hours before I left, and though they were resting only a few hundred yards from the field hospital, I did not know they were on the Peninsula. Trooper White was observing through a periscope a few days later when a bullet struck the upper mirror, and he was wounded in the left shoulder and wrist by flying fragments of glass, but he did not leave for some weeks, when he had a very severe attack of influenza. My brother was struck in the nose by a bullet about the 16th October, and was sent to the hospital at Malta two days later. He was hit on the chin by flying splinters of a bullet, but this was not a serious wound. He was very fortunate getting off so lightly. Trooper White, who was with me in the hospital at…near Cairo, a few weeks before Christmas, wished to be remembered to his friends and looks forward to the day he is free to return.

Though the evacuation came as a surprise to all, we were more or less pleased that Gallipoli was a thing of the past. We could have crossed the Peninsula, no doubt, but it would not have been worth the sacrifice of lives that such an operation would have entailed. But there is one thing certain – the Turks could not have driven us into the sea by force, as they often boasted that they would do. The whole campaign in Gallipoli seems to have been a case of the irresistible having met the immovable. It was no use sitting behind a brick wall and barking at the enemy. It is only a matter of time, money and men, until we are able to crush Germany. But we need thousands of men yet – in fact, I think it will run into millions, but England and the colonies will get the men and the money too! 8

The Gallipoli operation cost 26,111 Australian casualties, including 8,141 deaths. Despite this, it has been said that it had no influence on the course of the war.

Following his repatriation Jack Kenny went to work at the Meatworks as a clerk. However, in 1918 he re-enlisted with two other Riverstone men – Ulric Blacket and Sid Clark 9. These three sailed for England in June 1918 as part of a contingent known as “Carmichael’s 1000”. 10 However, by the time they arrived the war was drawing to a close and Kenny was not posted to France. He arrived safely home in November 1919 – the “last of the Riverstone batch to return”. 11

The three Light Horsemen – Bert Kenny, his mate Frank White and Austin Smith, all returned to Egypt where they resumed their role as mounted troops. The Light Horse fought the Turks in Egypt and Palestine and Austin Smith took part in what is generally acknowledged as the last great cavalry charge in modern warfare. The attack took place at Beersheba. It was described by one eye witness as “the bravest, most awe inspiring sight I’ve ever witnessed, and they were…yelling, swearing and shouting. There were more than 500 Aussie horsemen…As they thundered past my hair stood on end. The boys were wild-eyed and yelling their heads off”. 12

Austin Smith later wrote: “If I live to be a hundred I’ll never forget it…The Turks were strongly entrenched in trenches, redoubts and they had plenty of machine guns and field guns. But we went through and over the lot some of us galloping right under the muzzles of the guns and jumping trenches with Turks firing at us in mid air and right through the main streets…I’ll never forget the roar of the shells and bombs etc exploding as we galloped up the street.” 13

Following the defeat of the Turks Bert Kenny and Frank White returned to the Dardanelles as part of a 7th Light Horse garrison force. The irony was not lost on Bert who remarked that “he little thought they would sail in through the Dardanelles when he left there, wounded, 3 years [previous].” 14

After surviving the landing through to the evacuation of Gallipoli, the indestructible Bert Davis was sent to the Western Front where he remained until the Armistice. He returned to Riverstone at the end of 1918 and commenced farming some land at Schofields.

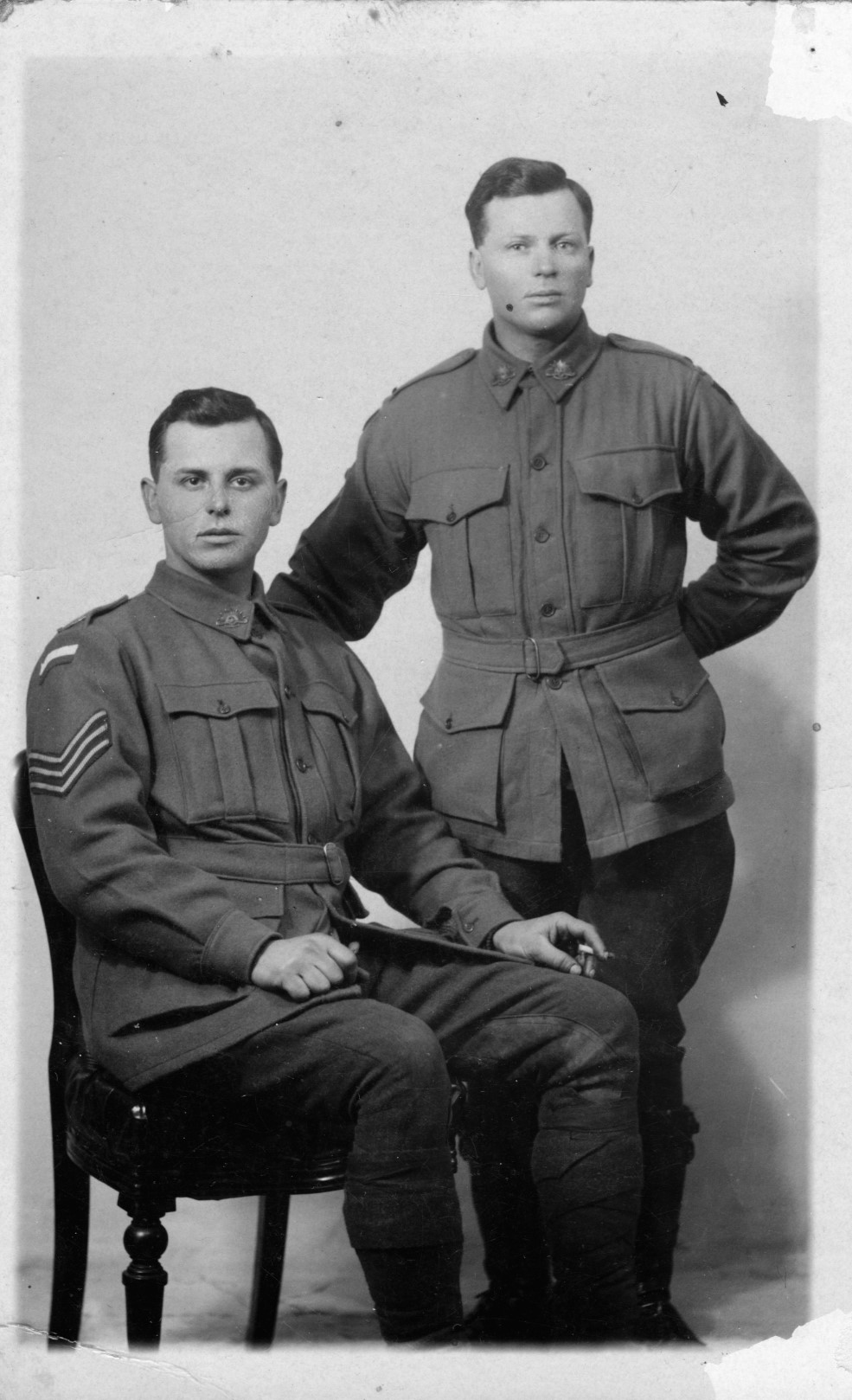

Photo courtesy: Ron Mason.

Photo courtesy: Bev Harm

References

- Recollections of Maurice Brian Mason [1906-1990] told to the author.

- Figures based on a list compiled by Rosemary Phillis from the various Riverstone and District Honour Rolls, the Windsor and Richmond Gazette and information supplied by local residents.

- Windsor and Richmond Gazette, 21st August 1914.

- Frederick William Clark enlisted 11th August 1914 and Herbert Davies on the 28th August 1914, WW1 Embarkation Roll, AWM, Canberra.

- Before Gallipoli – Australian Operations in 1914, Semaphore, Issue 7, August 2003.

- Encyclopaedia, AWM, 27th May 2007.

- Private Archibald Robert Showers, No 2209, 2nd Infantry Battalion, Killed in Action 6th August 1915, Roll of Honour, AWM, Canberra.

- Windsor and Richmond Gazette, 3rd March 1916.

- Windsor and Richmond Gazette, 21st June 1918.

- Captain A. C. Carmichael MC, 36 Battalion AIF, raised 1000 recruits for the AIF in 1915. He was wounded on the Western Front for the second time, on 4 October 1917, and returned to Sydney in February 1918, where he proceeded to successfully raise another ‘Carmichael’s thousand’. Carmichael rode at the head of his ‘thousand’ when they left Sydney on 19 June 1918. He arrived in France in late September, by which time the war was coming to an end, so he returned to Australia.

- Windsor and Richmond Gazette, 7th November 1919.

- Account by Private Eric Elliot, “Defending Victoria”, website.

- Austin Smith, Letter dated 23rd November 1917.

- Windsor and Richmond Gazette, 21st February 1919.