by Shirley Seale

In the Journal last year, Rosemary wrote about the current effects of the current pandemic. This is a look back at the history of the 1919 pandemic.

Celebrations of the end of World War I were turned to despair when the deadly pneumonic influenza began to rage around the world. In New South Wales optimism caused the Department of Local Government and the Board of Health to inform the local Council on 17th January 1919 that the epidemic had been practically wiped out and there was a much brighter outlook now. The Board was preventing the establishment of an Inoculation Department for the present time and asked what action the Council had taken to prevent the spread of the epidemic. [i]

By January 28th four cases of the pneumonic influenza were reported in Sydney, each having been contracted in Melbourne and the Government began to realise the extent of the contagion. A member of Parliament in NSW declared ‘Victoria, by its neglect to have itself declared an infected state by the Commonwealth, has allowed infection to become widely distributed amongst its population and by its delay to act has also brought about infection in this state.’ New South Wales acted swiftly and imposed preventative restrictions in Sydney and the County of Cumberland, which included Riverstone. The restrictions bear an uncanny resemblance to those we lived through in 2020 and now in 2021.

Traffic was stopped at the borders and a quarantine of seven days was imposed on all travellers by land or sea. All places of public entertainment were closed, schools, church services and meetings were prohibited. (Teachers were still being paid and 1200 volunteered at the emergency hospitals – there was no on-line teaching in 1919).

Masks were made compulsory by an order of the Premier, William Holman on 31st January and fines were imposed for non-compliance. Travel within the state was not restricted and many people travelled to the Blue Mountains where they thought the fresh air would keep them healthy.

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales and Courtesy copyright holder. Wentzel family.

That month, Sir James Cantlie, Surgeon to the Seaman’s Hospital and Lecturer in Surgery at the London School of Tropical Medicine, announced that the only valuable antidote for the new influenza was alcohol, and the scarcity of alcohol, said Sir James, is a disgrace to the controlling authorities. This ray of hope was soon refuted by Dr Gwynne Hughes, one of Sydney’s eminent medical men, who said ‘so far as a stimulant is concerned, people who are used to taking them should continue to do so, but not to excess!’

The local trotting meeting to be held at Londonderry was postponed in the first week in February.

Usually in Riverstone, as the soldiers returned home at the end of the war, the railway station was decorated, a band was playing and people crowded the station area with banners and flags. However the welcome home for Private Wilson was indefinitely postponed in February due to the restrictions and by July when Corporal Marlin returned, the band was absent because practically all of the members were suffering from influenza. [ii]

Mr R.W. Setchell, a Riverstone clergyman, had sent a postcard to Mrs John Wheeler of Bourke Street telling of his voyage in a troopship. Mr Setchell was in good health, but 600 of the 800 men on board had been stricken down with the influenza scourge, which ‘authorities in this country are now engaged in a campaign against’.

On Saturday15 February, the Daily Telegraph on page 10 reported ‘so far the Hawkesbury District is free of influenza but the health authorities of the municipality are leaving nothing to chance. Masks are universally worn and the people are co-operating loyally to keep the scourge out. A Vigilance Committee, comprising aldermen and four members of the hospital committee has been formed and at their first meeting decided to utilise the public school as a temporary hospital should the occasion arise. An inoculation depot has been opened in Windsor and another is to be opened in Riverstone immediately. All the hotels, schools and churches have been closed and public functions and meetings postponed until the danger is passed’.

On a lighter note the Windsor and Richmond Gazette (the Gazette) that month wrote ‘The most comical sight of the season was a courting couple, who wishing to be quite up-to-date, squatted on the grass in McQuade Park, Windsor and chatted away for dear life, wearing their white influenza masks. One would imagine that the masks knocked all the poetical sentiment out of courting life but apparently it didn’t for casual passers-by could hear the muffled lovey-dovey and suchlike spoony vocabulary at the usual quick intervals’.

At the end of March, the Government announced that the Sydney Show was abandoned for the year and added some further restrictions. No person could remain in a hotel bar for more than five minutes and people were urged to take whatever precautions they could to prevent contagion. The Showground buildings were to be requisitioned for the purpose of hospital accommodation for patients. The Show Society raised no objection while pointing out the considerable financial losses to all concerned. [iii]

On Friday 25 April, our first Anzac Day, the Gazette commiserated with Dr A. C. Johnston, who was kept busy owing to so many people having contracted colds and influenza. Some of the residents have made a move to fight the influenza in case it breaks out in a virulent form’. The doctor was assisted in looking after the patients by Mrs Crisp, Mrs Wallace, Mrs Symonds and Miss Shepherd but needed more help. ‘There are several cases in town. The fitting and equipping of a local hospital seems to be out of the question though the next best way of fighting the pandemic is nursing in the patient’s own home and strict isolation regulations’.

A tennis match went ahead at the request of the Captain Mr Gallen although his sister had recently died and the sad case was mentioned of Byron Cheadle, son of F. Cheadle of Marsden Park, who was buried the previous Saturday and whose wife died only two days later. The ‘scourge’ as the paper called it, was starting to be felt in the district.

In April also, the Health Inspector, Mr T.W. Jago, reported to Blacktown Council that an outbreak of pneumonic influenza had occurred at Riverstone and Plumpton. Altogether there were fifteen cases, four were in Riverstone, two in Plumpton and nine in Windsor. The doctor stated that all was being done that could be done. Mr Cunningham, a member of the Administrative Board in Sydney, announced he had been sent to Blacktown to open an emergency depot forthwith and suggested the appointment of the head teacher at Blacktown Public School, Mr McCredie as Depot Master. A sub- depot would be opened at other parts including Riverstone. It was resolved to make application to have all public telephones made available at all hours as far as was practicable. A motor ambulance would be provided for use, the Department would pay the salary of an assistant health Inspector and meet all reasonable expenses in fighting the pandemic. [iv]

Miss Renie Vidler of Riverstone is going as a nurse in training at Wellington Hospital, reported the Gazette on page 9 of its 4th April Edition. ‘The lot of a nurse is not as easy as some might be inclined to believe. Women who perform these duties have great responsibilities on their shoulders. The recovery of the patient is often due to the tender care and cheery manner of the nurse. In addition to the responsibility a nurse is often exposed to great danger of contracting a deadly infectious disease – the present scourge for instance that has broken through the quarantine gates of this Commonwealth. A great many nurses have been attacked by the deadly disease of pneumonic influenza’.

On 23 May 1919, the Gazette was able to report that all influenza cases in Riverstone were progressing well and no fresh outbreak had been reported. An advertisement on page 3 of the Gazette on 25th June read ‘For influenza, colds, take WOOD’S GREAT PEPPERMINT CURE’, but two days later on page 4, ‘There is an increasing amount of sickness throughout the district, some of the cases being serious. A death from Pneumonic influenza occurred in the Richmond Emergency Hospital a few days ago. There are other suspected cases of the scourge’.

In June and July some of the young men in Riverstone were becoming victims and their deaths were reported locally. Arthur Rumery, son of a well-known local family, died of the influenza on 30th June, just days short of his 32nd birthday and his cousin, Cecil Stranger, died on 3rd July. His sister Elsie Stranger had started nursing but all the family became ill and she was sent home to look after them. She said ‘the flu seemed to take the strongest while the weak pulled through’. [v] Bertrand Alcorn, a popular young man of twenty-five years, died at Riverstone on 6th July and Arthur Sherwood, of Rouse Hill, a local cricketer, ‘a man of apparently strong constitution in the prime of his life’, fell victim to influenza the same week.

Photo: Rumery Family Collection

There was much sickness in Riverstone and the Gazette wrote that it had made ‘many sad homes, for several deaths have occurred. Scarcely a house has missed the visitation. At Mr George Freeman’s home, nine of the ten inmates were down together’. [vi] One of the saddest cases, reported in the same edition, concerned Mrs Sanders, the sister of Mrs Crisp, wife of the Riverstone Police Officer. She had come to Sydney from Broken Hill with her little children to meet her husband, Signaller W. Sanders who was to disembark from his troopship the next day. Mrs Sanders contracted the influenza and died three days after arriving to greet him. Sympathy was expressed for Mrs Crisp, who had not been well.

Mr Frank Fenwick of the Post Office had to be sent to Parramatta District Hospital by motor ambulance and Private Kirwan was still in Egypt after being too ill with Influenza to travel home, but was reported as recovered now. Also recovering was Arthur Sturman who had been in critical condition and Mrs Wiggins, who had been despaired of.

Recognising that the pandemic had adversely affected the finances of hundreds of workers, the butchers of Sydney suggested that meat be distributed free to the needy. Riverstone Meatworks, together with other wholesalers, immediately agreed to the donation of 60 pounds worth of meat to be cut up and distributed by the Meat Board at various Influenza Relief Depots. About six tons of meat was donated. [vii]

The Gazette praised the Sydney Health authorities for having a ‘proper realisation of the seriousness of the plague, but were scathing about ‘our brotherly Victorian brothers’ whom they blamed for sending a second dose along to NSW. Victoria is getting just what she might expect from her criminal indifference’. [viii] Between March and August 1919 almost 40% of the NSW population had contracted the disease and 6387 of them had died.

The Commonwealth Serum Laboratory had manufactured a vaccine, which was provided free of charge at Inoculation Depots, but, just as today, it was not universally accepted, was not compulsory, but seemed to lessen the effects of the sickness in those who had been vaccinated. Many of out local citizens queued up for the ‘jab’.

On 11 August this advertisement appeared on page 3 of the Windsor Richmond Gazette:

REFINE gives a stronger resistance during epidemics. When diphtheria, influenza, typhoid, acute colds and other epidemics are prevalent……REFINE gives fighting power to the red corpuscles in the blood …… etc. Sold by chemists and grocers.

No firm could advertise like this in 2020 or 2021!

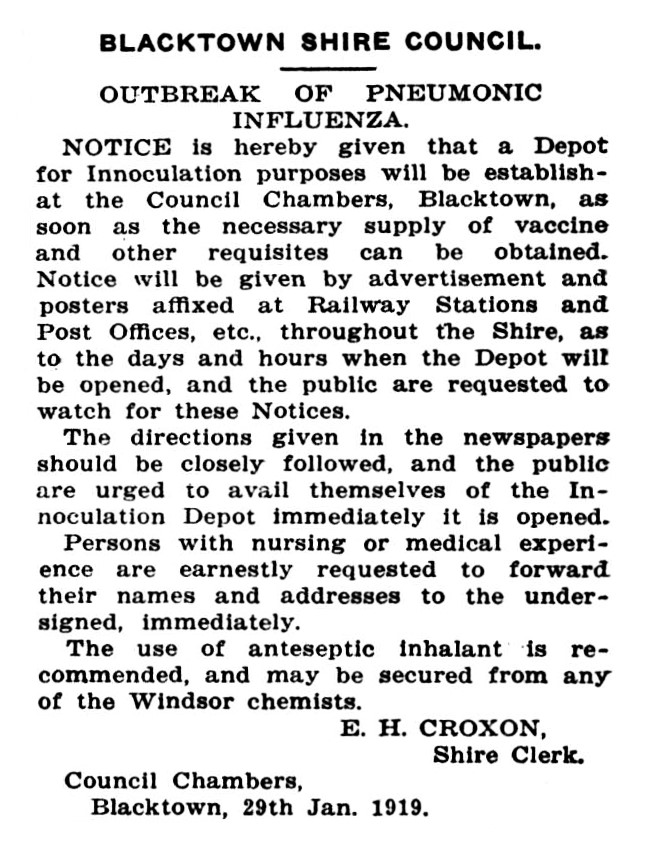

Inoculation Depots were established and advice given to residents through notices in the Gazette of 7 February 1919, such as the one below from the Blacktown Shire Council.

A few days later, on 15th August the Windsor Richmond Gazette could report that there were no new cases of pneumonic influenza at Richmond Emergency Hospital and those brave women who offered their services have returned to their homes.

In December 1919 a final report for the year read: ‘Miss E. Shepherd, who was a most prominent worker among the influenza patients in Riverstone, was recently made the recipient of a silver-mounted hairbrush and comb, in recognition of her valued services during the epidemic. Miss Shepherd, in her modesty, does not think that her work is worthy of recognition in a public way and has decided not to accept the gift. [ix]

[i] Windsor Richmond Gazette, 17 January 1919, p. 10.

[ii] Ibid., 7 February 1919, p. 9; 4 July 1919, p.9; 28 Feb.,1919, p. 2.

[iii] Sydney Mail, 2 April 1919, p. 13.

[iv] The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, 26 April 1919, p. 11.

[v] E-mail from Rosemary Phillis.

[vi] Windsor Richmond Gazette, 11 July 1919, p.2.

[vii] The Sun, 16 July 1919, p. 9.

[viii] Windsor Richmond Gazette, 7 February 1919, p.4.

[ix] Ibid., 9 December 1919, p.3.

Information on statistics was sourced from records.nsw.gov.au/archives/collections-and-research/guide-and-indexes/galleries/Spanish-flu-1919