by Rosemary Phillis

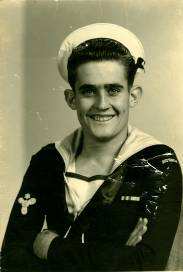

John McHugh joined the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) in 1950, when he was 17 years of age. He completed what was known as ‘Boys Time’. He was a stoker mechanic, (later known as a mechanical engineer), working in the engine room of the ships. He was posted to Flinders in Victoria for his initial training.

The RAN routinely moved men from ship to ship, wherever they were needed and to gain more experience. John served on a number of vessels including HMAS ‘Condamine’, HMAS ‘Voyager’ and HMAS ‘Melbourne’ (SEATO 1963). These ships sailed in both Australian and Asian waters.

John served in the RAN during the Korean War, from 1952 to 1955. The role of the RAN included patrols, shelling and supplies. Interestingly, John’s brother, Greville George McHugh served in the Korean War in the Army.

John spent his time during the Korean War on HMAS ‘Condamine’. In 1997, one of his shipmates, Vince Fazio, released a book called, “HMAS CONDAMINE The Story of a Uniquely Australian Frigate”. The following excerpts give some insight into some of the things that John would have experienced during his time in the Korean War.

In June 1952 the ‘Condamine’ sailed from Australia to Kure in Japan. She commenced her first war patrol on 3 August 1952, in the Haeju area on the West coast of Korea. Initially the ‘Condamine’ had the task of “looking after rail traffic”, which meant trying to shell trains as they ran along the railway line on the coast. According to Vince, ships would either lie “doggo” at set points, hoping to catch a train between tunnels, or, alternatively, fired away to destroy rail lines at positions where repair work would be very hazardous to carry out.

The ‘Condamine’ did have success in firing on a train, but there was a twist to the story as Vince records: “Some minutes later a southbound train was observed making a dash, but with the CONDAMINE firing continuously at a particular point, two obvious hits were observed and the train was stopped. The elation of the victory was short lived however, when half of the train continued south, whilst the rear half backed into cover. LCDR Savage observed, that it appeared the North Koreans had catered for such an eventuality by having a locomotive at both ends of the train, enabling what was left of the train to clear the danger spot….”

On 22 October 1952, the ‘Condamine’ was damaged in a collision with HMS ‘Cossack’ which was attempting to transfer across mail for the ‘Condamine’. Damage to ‘Cossack’ was minor, but as Vince Fazio records: “The damage to the ‘Condamine’, although only about five feet below the deck edge on the bows, would have allowed a substantial amount of water in. As an interim measure, some damage control measures were taken by Joiner Vince Fazio with Stoker John McHugh assisting… The hole was successfully plugged and shored…”

The freezing cold Korean winter weather created some very difficult conditions on the ship. John McHugh put together a photograph album of his first years on the ship. Several photos show the top deck of the ship covered in ice. Vince recalls: “Snowfalls were almost continuous by now and for the majority of the ships company, the sight of a foot of snow on the upper deck was a novelty. The time honoured practice of snow ball fights was quickly established.”

Warm clothing was a necessity, even down in the engine room where John was. Vince describes: “Speaking of suitable warm clothing, which we weren’t, but will, the author recalls the dressing routine. Normal underwear, with a string singlet under the Chesty Bond, Long Johns, socks, shirt, long sleeved jumper, working dress trousers, seaboot socks, seaboots, single breasted coat, wool gloves, outer gloves, duffel coat and balaclava. So far so good, but when on the upper deck trying to carry out routine repairs, etc., one could hardly move for the sheer bulk and weight of the clothing.”

The Boiler Room watch keepers had to ‘rug up’ as well. Seems hard to believe, but when under the air flow from the forced draught fans, pulling in extremely cold air, such clothing was as necessary as it was anywhere else on the ship.

In addition to her war time patrols, the crew of the ‘Condamine’ also provided support to locals on some of the islands that they visited. At Christmas in 1952 after taking up collections on board, they purchased toys, which were distributed, to children at an orphanage at Taeyong Pyong Do.

When the crew were advised that the ‘Condamine’ was returning home, they started to stock up on souvenirs as Vince describes: “Up to now, purchase of ‘rabbits’ (souvenirs, etc.) had been discouraged so as not to clutter the ship in case of emergency. Now, all the lay bys, and last minute shopping was open slather and all purchases were brought aboard and stowed in the nooks and crannies, which had been earmarked for the purpose! Sailors seem to have a knack of being able to stow items in spaces where the average person would think it impossible.”

Hospitality was returned to the various Army messes who had hosted the ship on differing occasions, in particular the Army mess at Hiro. There are many stories and fond recollections of the hospitality by Army and Japanese civilians, who held the Australians in high regard locally.

During her time the ‘Condamine’ took part in shelling activities, escort duties, evacuation of wounded Marines, supported minesweepers amongst other duties. On 20 April 1953, ‘Condamine’ arrived at Garden Island, after ten months away.

According to Vince, after their arrival … “LCDR Savage was interviewed on three occasions by the ABC in a matter of days, giving a good account of his ship and her company. The Korean War did not attract the emotional outbursts that were prevalent during the Vietnam conflict. It has been described as the Forgotten War, as nobody apart from those who served in it, seem to care.”

The ‘Condamine’ returned to the Korean area again in 1955 for Peacekeeping duties and continued in Navy service until 2 December 1955, when she “hauled down her White Ensign for the last time”. Appropriately, her motto was “We Fight for Peace”.

In 1953 John married his wife Moira, who shares with us memories of life as a Navy wife: “I was working in Sydney. Accommodation was difficult to find and I was sharing half a house with three other girls. The landlord was a Lebanese man and I got on all right with him and was able to stay living there until he redeveloped the building. When John and I married we had a small wedding and such was the custom at that time that I invited the landlord and one of the other people who lived in the building.

John was in the Navy and away for long periods of time. If they were based down at Jervis Bay a number of them would hire a car and come up for the weekend. When our first baby, Robert, came along, it was difficult for me to find accommodation. Landlords didn’t like renting to people with children. I didn’t understand the reason, but while you were looking you didn’t take the baby or anything like a bunny rug that might give them the suspicion that you had children.

I managed to find a place at Rushcutters Bay, on the third floor of a building. There was no lift, three flights of wooden stairs, limited lighting and I had to share cooking facilities. The view from the window was of a coal dump. It was difficult to carry everything up the stairs all the time, especially with the baby. I used to cook on a small spirit stove to make things easier. At the time I was just glad to have a roof over my head. One night there was a fire in a mattress in the room across the hallway. There was smoke everywhere. Soon after that I decided that I had to get out of there.

I moved around with the children after that, living with my parents on the Northern Tablelands and John’s parents at Riverstone. Finally with the assistance of War Services, we were able to purchase a block of land in Regent Street Riverstone and build a small house, where I still live.

John didn’t talk much about his work in the Navy. I just accepted that was the way it was and got on with things. John always liked me to go down to Garden Island to see him off when he went to sea. I would also go down when he came home, something that was a little more difficult when the first baby came along. In those days you’d dress up and wear your stilettos to look your best, not very practical around all the metal and especially if you got to go on the boat.

I remember going on the boat one time and having to go down a ladder. John said to me “you go first”. When I asked why, he said that was the way it was, so that a man couldn’t look up your dress! If I was to go up a ladder, he would go first! That’s the way it was.

John loved to buy things when away, always the biggest and the strongest he could get. Amongst other things he brought back a heavy ironing board and a set of saucepans. He brought a dinner set, but I didn’t get to see it as they went through a hurricane and it got broken. Having been on board the ship and seen how little space there was, I never understood where they stored these ‘souvenirs’.

Sometimes they had family days when the boat was in Sydney. I recall going down to Garden Island when he was on the ‘Melbourne’ when it was home for Christmas. It was a large ship and someone came up with the idea to fill the lift well with water. They then put in a canoe and gave the children a ride in the canoe on the water. They also showed movies in the hanger. It was pitch black and I admit that it made me feel claustrophobic, but I soldiered on, you didn’t want to embarrass your husband at any cost.

They had family day out on the harbour on the ‘Voyager’. I wasn’t able to go, so John took one of our children and a friend. I was worried about the children getting seasick. John told me not to worry as the Captain wouldn’t go out of the heads if the weather was rough. The kids went, had lots to eat and of course the Captain did take the boat out through the heads, it was rough and you can imagine the result. All those sick children!

John served on the ‘Voyager’ before moving to the ‘Melbourne’. Tragically in 1964, the

‘Melbourne’ collided with the ‘Voyager’, cutting the ‘Voyager’ in half and killing many men.

The next morning someone came to visit when they heard the news on the radio, and the phone continued to ring with others. There was nothing that I could do, there was no point in trying to ring, I knew that eventually either John would contact me, or the Navy would. John never said much about it, apart from when it happened that the call went out “Battle Stations” and he went to the engine room. I asked him how he would have known if the ‘Melbourne’ was sinking, he said he would have seen a ‘shadow’ on the floor near the stairs.

It must have been a very painful time for him, for having served on the ‘Voyager’, he knew many of the men who had been killed. It was a smaller boat and they got to know their fellow sailors. The ‘Melbourne’ was a lot bigger and you didn’t get to know people all that well.

I remember one other time being at home having breakfast with my son Robert and John’s sister Joan, when I heard something about someone on the boat that John was on having been taken by a shark while swimming. Once again there was nothing I could do but wait. I was relieved to receive a telegram from John basically saying “Not Me”. He later said it was a bit disconcerting; the cook served fresh fish for tea that night.

John finished his first time with the Navy. He tried working in the local butchers’ shop to become a butcher, but didn’t like it much. He came home one day, told me he had quit and the next thing he went out, came back and told me he had enlisted again. My stomach dropped, as I had become used to him being at home, but it was what he wanted to do.

John travelled to many places with the Navy. He went to Japan several times and once brought back a series of Japanese pop records. The girls used to listen to them and when he was home, as he came across the paddocks, he’d whistle one of the tunes and they’d know he was coming.

John had injured his back while in the Navy, playing football on one of the islands. Whenever they were close to an island, they liked to get the men to get off the ship. Sports such as football games were a good way to get exercise.

Although John didn’t talk much about his time in the Navy, he did mention things from time to time. I know that during the Korean War they had close contact with the Army and he used to meet up with Ron Bull, another local who lived in the same street in Riverstone, and had joined the Army.

After the war, John’s brother George told me more about what went on in Korea. John had put together a photo album of his first years in the Navy. It was George who got out the album and told me all about the places in the pictures. John just went outside and played with the children.

Over the years his back injury got worse. John rose to the rank of Petty Officer ME, before being discharged in 1965, after being assessed as medically unfit due to the back injury.”